Written by Aaron Barnes, Bachelor’s of Arts, History

Introduction:

Heritage seems to be something that is important to people and always has been. People have a natural fascination with who their ancestors were, what they did and how they accomplished it. In modern Europe and the United States, the “Celts”, “Gauls” or “Gaels” evoke a sense of international heritage and revive a fascination with the past. The La Téne culture proved to be as enigmatic to ancient historians as it is to modern archaeologists today; however, due to the collaboration between literary sources and material culture, we can identify traits that pertain to the ethnic identity of this culture. Since contemporary sources label these peoples under umbrella terms, one could easily be misled into believing that these people are one large cohesive group; this is far from the case. Just how different and similar were these people? How can historians work with archaeology to validate or discredit ancient literary sources? Just how great were the distinctions between Germans and Gauls, both barbarians of temperate Europe? With a compilation of sources at our disposable these questions are able to find answers.

Gallic identity can be compared and contrasted through examination of certain secondary indicia. Some of my arguments are stronger than others, the Gallic religion centered around Druidism, their burial practices, their language and dialects, their arms, armor and battle tactics, and their habits and geographical location. I will argue that the Celts are a cultural group with regional ties, rather than a whole nation.

Historiography and Archaeology:

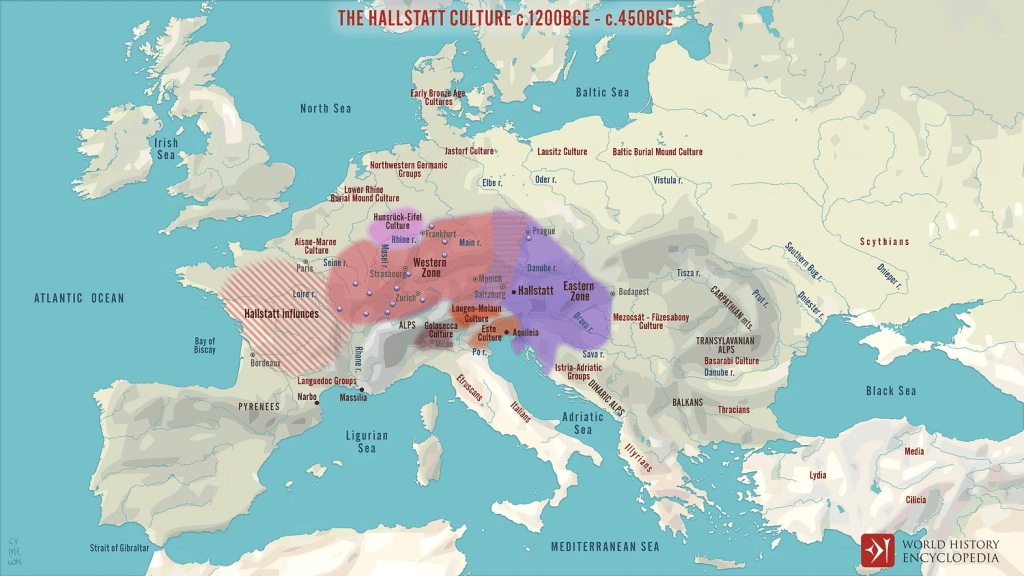

In order to frame the arguments presented by the thesis, we must first examine the history and historiography of these people. The temperate regions of Europe have been connected with the Ancient Mediterranean since the Bronze age. We know this due to the bustling amber trade from Northern Europe into Greece and around the Mediterranean. The groups involved in the trade and people along the trade routes have left behind evidence of their interactions, settlements and material culture. In 1846 John Ramsauer, an Austrian miner and director of excavations, discovered a pre-historic cemetery near Hallstatt, Austria. Upon excavation of this site, many artifacts were discovered in the graves as well as within the salt mines that surrounded the landscape and were used by these early predecessors to the La Téne Culture.

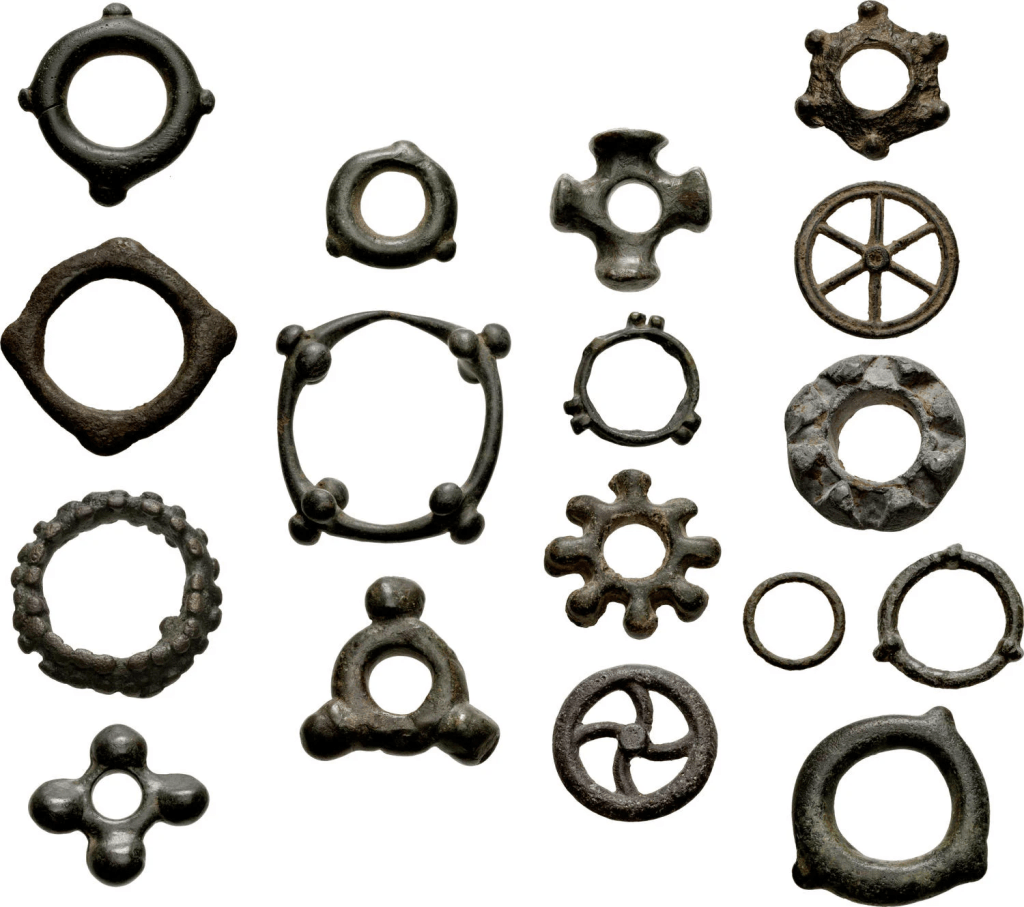

The Hallstatt culture proper is defined as the period from 800 – 450 B.C. and is based on inhumation and cremation burial practices coexisting, weaponry forged from both bronze and iron and a unique style of brooches. During the 7th century B.C. when Greeks began to create apoikia around the Mediterranean, archaeologists noticed a shift in culture and settlement with the Hallstatt culture. Around 450 B.C., the archeological record becomes scarcer and archaeologists see signs of settlement abandonment and grave robbing. It is also around this time that people with a similar material culture and language (as demonstrated by the Lepontic Celtic inscriptions) appear in the west, near the Rhineland and north of the Alps. The areas near these trade routes now became enriched, which created powerful chiefdoms to control the distribution of luxury goods from the Etruscans and Greeks into deeper “Celtic” territory. Noted for their intricate spirals and distinct style of art and metal work; is when the La Téne culture became characterized, the period that preceded Julius Caesar’s annexation of Gaul and the overall Roman Imperial period. La Téne culture during the 4th century spanned as far west as the Iberian Peninsula, north to Scotland (and later Ireland) and as far east as Asia Minor. This culture saw the development of oppidas, or hill-top forts,in their villages that Julius Caesar frequently cites in his Gallic Wars. During these series of migrations, the Gallic people spread their culture throughout Europe and often came into violent contact with the people in their paths; sacking Rome in 395 B.C. and Delphi in 279 B.C. Most of the primary sources written by Greeks and Romans about the Gallic tribes were from this era. Iron Age historians constantly remarked on the battle prowess of Gallic people. Diodorus mentioned the commendations that Gallic mercenaries received who fought with the Spartans against Thebes. Contemporary sources often contain intense bias, painting the Gallic people as barbarians amassing on the borders of civilization; they were however, civilized in their own right. However, once most of these Gallic tribes became subjugated by Rome, their culture was disrupted intensely and they essentially assimilated into the Roman Empire.

Greek and Roman ethnographers and historians defined these people as Keltoi and Galli, people who lived north of the Danube and in modern day France, Britain, the Alps, Northern Italy and later Anatolia. Their defining characteristics were their light hair, bright eyes, stature and strength. Also, they were known to paint themselves, follow druidic religion and be wild, untamed drunks as well as powerful warriors. Michael Dietler does not believe the Gallic people are a single ethnic group at all, but believes that their material culture and interactions with their neighbors influences their culture greatly[1]. Benjamin Isaac attempted to define the concept of racism in antiquity through a cultural lens rather than racial. He examined the Gauls in a broader context loosely defining them based on geographical location and their behavior and how it effected the way Romans and Greeks defined them. Leif Hansen is an archaeologist who traces the consumption patterns of Gallic people. He does this to conceptualize the cultural changes through time that Celts experience. Ursula Rothe is another archeologist who focuses on consumption, but more specifically she attempts to define Gauls by the way they dress, and how different influences effect them. Charles Joseph O’Hara defines the ethnogenesis of Gallic people based on their interactions with neighboring people. He argues compellingly and uses material evidence by Christopher Howego, who focuses on Gallic coinage and its influences, to prove his points.

Indicia to Classify Gallic Identity:

McPherson says that there are indicia which contribute to a group’s ethnic identity. As outlined in the thesis, I believe those to be the most relevant indicia to evaluate the La Téne culture also known as the Celtic culture. Since primary sources written by Gallic people are virtually non-existent during the 1st century B.C., we must rely upon contemporary ethnographers from Greece and Rome. These are naturally biased since they are an outside perspective written by people who were generally adversarial towards the Gallic tribes. However, considering the high volume of interaction between Gauls and other groups, much of the assertions recorded cannot be entirely false. Secondly, the evidence that is harder to dispute is the material evidence that these people left behind. The archaeological record is comprehensive enough to deduce certain aspects about Gallic society in its entirety, and regionally over periods of many years. When academics and scholars combine literary sources with physical evidence, we obtain a clearer image of the society in question. The evidence selected for this journal relies upon ethnographic written accounts by Julius Caesar in De Bello Gallico during his campaigns in modern day France and southern Britain in the mid 1st century B.C. He spoke in detail about hostile tribes and allied tribes alike, intended for a common audience back home in Rome. He attempts to classify the traits of these people and hypothesize why other tribes were fiercer or tamer than others. His first hand accounts during battle or about the political intrigue he faces are invaluable. Secondly, Tactius’ Germania mentioned traits of Germans and other people along the Rhine. Germans, Celts and Gauls are all Roman or Greek terms used to classify these people, they are not used by these groups themselves. Therefore, in some of my research I have found similarities that suggest diffusion of culture among Gauls, Greeks, Iberians, Romans and Germans who lived in proximity to each other. Finally, archaeological evidence of weapons and armor, luxury goods, burial sites and bodies provides a solid back-bone to conceptualize the lives of Gallic people. When the material evidence works in tandem with literary accounts, we can be confident in our deductions. However, when they do not work together, we must imply different possibilities and consult works by experts on the subject.

Gallic religion remained very similar among the tribes, despite being separated from some tribes by many miles. Theonyms for different deities appear throughout Gallia, Brittania, and near the Danube. For example, Lugus, Lugh and Lleu are all names referring to the same deity[2]. Julius Caesar described this deity as the Gallic equivalent to Apollo and the chief god among the Gauls[3]. Additionally, Celtic people across the diaspora had a spiritual affinity with the number three. According to Roman poet Lucan, Teutates, Taranis and Esus were the names of the three most sacred deities to the Celts[4]. In regards to polytheism, it is understandable why we see ethnographers relate some other ethnic groups deities to their own. According to Lucan in Bellum Civile, Taranis was associated with Zeus, since he was the god of thunder, Teutates with Mars and Esus with Mars respectively.

The polytheistic and animistic nature of Druidic religion was something that linked tribes together during ritual, diplomacy or war. Caesar is our most well documented source on the druids of the Celts. He wrote that the druidic position and authority originated in the Britannic Gallic tribes and diffused southwards towards the rest of the Gallic world[5]. Unfortunately, due to the lack of endemic records from the Celts themselves, we are unable to affirm this assertion. However, since the Neolithic era, the British Isles have attracted northern Europeans for religious regions as archaeology of migration patterns has shown. Druidic customs and mysticism has been noted and proved by archaeology against contemporary accounts. They were said to have supervised human sacrifices, were involved in healing, and education. Among certain bog bodies discovered, like the Tollmund Man, ritualistic killing has been noted. Also, mistletoe has been described as sacred to the Celts, traces of this plant were discovered on the corpse.

This is not the only instance though; furthermore, analysis of lamps, incense burners, and other artifacts from the La Téne culture in Celtic territory contained traces of mistletoe and other sacred plant residue and ash[6]. From this evidence we can deduce that these similar superstitions existed across many different tribes. Druids were selected from different tribes and sent to be trained in Britannia, which upon completion in the oral traditions of druidism, would wander the tribes performing their duties. According to Julius Caesar, druids acted as intermediaries between tribes and were respected by all despite potentially being from an enemy tribe.

“they have opinions to give on almost all disputes involving tribes or individuals, and if any crime is committed, any murder done, or if there is contention about a will or the boundaries of some property, they are the people who investigate the matter and establish rewards and punishments. Any individual or community that refuses to abide by their decision is excluded from the sacrifices, which is held to be the most serious punishment possible. Those thus excommunicated are viewed as impious criminals, they are deserted by their friends and no one will visit them or talk to them to avoid the risk of contagion from them. They are deprived of all rights in court, and they forfeit all claim to honors.”[7]

The way Caesar described the role of druids creates a thread that connects the Gallic people in their entirety. If they did not share a common belief and respect for the druids, and by extension the gods, what obligated the Gauls to honor druidic edicts?

The burial practices of the tribes varied, but were usually centered around practices of inhumation, cremation, and mummification. The predecessor to the Halstatt culture was known as the Urnfield culture. This is because of their peculiar burial practice of cremation, then burying urns in mounds. La Téne nobles still continued this practice, which was remarked on by Roman and Greek ethnographers and has been verified by archaeology. Specifically, tribes in South Eastern Britain. They burnt their upper class dead on pyres with precious livestock and votive offerings, then scooped the ashes into urns which they buried in mounds. A notable type-site grave site is the tomb of the Lady of Vix. She was unearthed near Châtillon-sur-Seine, France in a mound grave with many votive offerings including the famous Vix Krater.

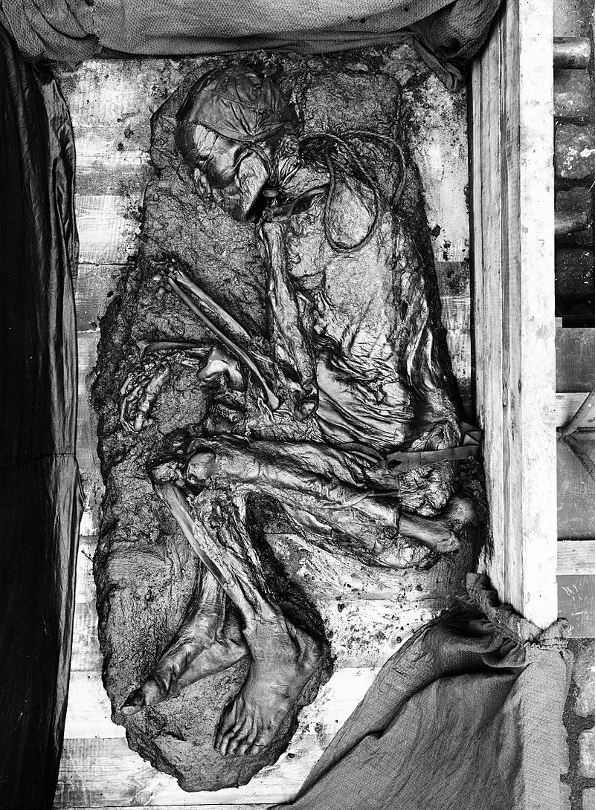

This site provides insight into the inhumation practices of wealthy Gauls. Where the environment allows, another notable form of burial practice could be observed. Ireland and areas along the Rhine, Celts and Germans would use peat bogs as areas to bury dead. Due to the chemical make up and lack of oxygen in the bog, mummification occurs. Tacitus in Germania and other Romans talk about how these people used the bogs. Tacitus stated that the Germans (although this term is ambiguous since “Celts” along the Rhine exhibited “German” behavior) used peat bogs as punishment. This may have been true, but archaeology suggests that victims were sacrificed ritualistically. This is due to the fact that they found votive offerings, mistletoe, torcs and jewelry in these bogs adorned upon the corpses[8]. Artifacts found in these grave sites, such as food, drink and slaves, suggest a belief in an afterlife, similar to Egyptian burial practices of preparing one’s journey. However, Caesar’s literary evidence and other funerary evidence of votive offerings suggests a belief in reincarnation.

Typically, when one thinks of a Gallic village, they probably imagine a powerful chieftain who was ordained to rule based on his lineage, this is a misconception. The Gallic tribes throughout the diaspora had different forms of governance, some not unlike Roman republicanism itself. According to Caesar and Strabo, the Celtic tribes had either monarchical or oligarchical governments. For example, the Bretons were ruled by several kings or chiefs who were supported by the nobles. The Caledonii though had a democratic government which allowed landowning freemen to vote on issues at council meetings. Furthermore, some tribes like the Arverni appointed a summus magistratus, or a chief magistrate. They were elected by priests and nobles and held office for a short period of time only. They were not allowed to leave the territory or the oppida[9]. Again, archaeologically it is hard to prove the validity of Roman claims on the matter; but when writing for a contemporary audience, there must be a hint of truth to the matter.

Caesar described the social structure of most Celtic settlements as well. He described a form of vassalage taking place with certain tribes in the region of Celtica; the soer-cheli and the doer-cheli[10]. The former being a free-vassalage and the latter a non-free vassalage. This was interpreted as the degree in which the vassals could dictate their own terms of their subjugation or participation in the union. The contract was usually formed around livestock and a tribe’s obligation to contribute troops or tribute to the overlord. An interesting pattern with this type of governance is that it took place in tribes that have had a long exposure to Rome. Geographically, the tribes mentioned resided near the Rhône river and northwest of the Alps, regions either allied or exposed to Rome. The Gallic tribes usually adopt traits from the peoples with whom they border which effects their culture and identity.

Language is not a reliable indicator of Gallic identity, it is too regionalist and diverse. The Celtic people did not all speak the same language; however, they spoke similar dialects or related languages. According to Julius Caesar,

“All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, those who in their own language are called Celts, in ours Gauls, the third. All these differ from each other in language, customs and laws.”[11]

Caesar was correct in this assertion that the Celts spoke different languages. It could be deduced that neighboring tribes may have spoken the same or similar languages, but a tribe like the Venetii or Allobroges would not speak the same language as the Dumnonii or the Aeudii, groups far from each other. On the other hand, all the tribes who have participated in druidic religion must have had multilingual members. Also based on certain theonyms, cognates or similar words are identified. O’Hara argues against a shared language though, “When the ancient Celtic languages first appear in the literary record, however, they are apparently already quite distinct from another. There is no reason to believe that all the different groups spoke the same single “Proto-Celtic” language, any more than that they considered themselves to belong to the same cultural group because of linguistic ties.”[12]

Based on Celtic inscriptions and epitaphs in the Greek or Latin alphabet, we can observe differences in language among the tribes. Today, in Brittany, Ireland, Scotland and Wales there are remnants of a Gallic language that was different than “mainland Gallic”.

The Celts of Europe and as far east as Asia shared similar weapons, armor, and tactics. There were a few variances in weaponry or battle style depending on the tribe, but generally Celts were a warlike people who had created a reputation for themselves for their battle prowess. The Gallic tribes typically fought amongst each other, according to ancient ethnographers, quite frequently. A tradition shared by the Gauls of Gallia and Brittania was to preserve severed heads to display their power and prestige. Diodorus and Strabo both documented this practice, but today, archaeology proves it. Skulls have been unearthed that had traces of conifer resin detected on them, which was a way to preserve them, confirming the practice.

Gauls were also able to unite in times of war or dire circumstances. In fact, Caesar said that

“If the Gauls were to unite they would be able to dominate the entire world”.

They shared enough of a common identity to unite against Caesar, representing foreign invasion, during the last phase of the Gallic wars when Vercingetorix, a noble from the Arverni tribe, created a coalition of tribes and nearly defeated Caesar at Alesia. Also, the tribes of Belgica were able to unite momentarily when they fought at the battle of Sabis. Most notably, Brittanic tribes under Cassivellanus, united at the battle of Gergovia and defeated Caesar’s legions[13]. Times of pressure from foreign powers can cause people with similar goals or lifestyles to unionize, which helps us realize aspects of their identity.

The weaponry and armor of the Celtic people shared many common traits. The metal was worked in a similar fashion, the La Téne style apparent, and their usage was well documented by foreign powers. The Gladius Hispaniensus, the sword equipped by the Romans, was adopted by the Romans during their contact with Celt Iberians during the Second Punic War.

The Spatha was also adopted from the Gauls, mainly who fought on horseback since this was a longer sword. The shields utilized by the Celts were elongated and slim, created in a similar fashion to most shields at the time. Wood glued together and covered with paint and hide, connected at a metal boss.

The Gauls supposedly fought naked sometimes, according to certain ancient sources, but nobles certainly fought wearing chainmail armor. This armor was an invention of the Gallic tribes and again, was adopted by the Romans due to their persistent interactions. Finally, the ornate ceremonial helmets worn by Gauls seems to be a tradition shared by many Gallic peoples.

The tactics varied among the Celtic tribes to an extent. Brittonic Gauls made use of war chariots, evidence in modern Austria suggested that tribes used chariots there too during the Hallstatt period, but the evidence does not come up during the 1st century. The tactic was based on psychological warfare and hit and run tactics; a driver would approach in a noisy chariot drawn by two horses, then drop off a skilled swordsman who attacks all around him, to be picked back up again to retreat. According to Caesar, Gauls on the mainland employed a similar tactic; they would ride a horse into the conflict with a companion who would jump off the horse, fight, and grab onto the mane and hoist themselves back up when their companion arrived[14]. Also, shield walls were mentioned at the battle of Brigante used by the Trevarii, Helvetii and Boii, this indicated drilling and usage of this formation in the past.

Conclusion:

The Celtic tribes of Europe have played a significant role in shaping history, but they have always been enigmatic to modern historians. The discoveries adding to the archaeological record and further review of our primary literary sources on the subject can provide historians with a clearer image of what it meant to be Celtic. The La Téne material culture provides the thread that we can use to link these tribal groups. Their identity seemed to have revolved around the usage of certain items, creating distinct art and style. Their religion linked the Celtic peoples together since it seemed most, if not all, of the Gallic tribes participated in druidic traditions. Language does not provide an argument for the identification of Celtic people in general. Where their languages are related, it does not mean they are discernable from tribe to tribe. Their weapons, armor, tactics, and ability to unite to confront powerful threats shows that they have enough in common with one another to form coalitions and alliances. However, the Celtic tribes also have much variety in their customs and traditions throughout the continent. In conclusion, the Celtic tribes are similar, but different. They were a dynamic people who are often misconstrued as a single nation, when in fact they are more like a cultural group, with their own regional identities.

Bibliography

Batinski, Emily E. “Lucan’s Catalogue of Caesar’s Troops: Paradox and Convention.” The Classical Journal 88, no. 1 (1992): 19-24. www.jstor.org/stable/3297740.

Benjamin, Isaac. “Gauls.” In The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, 411. PRINCETON; OXFORD: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Dietler, Michael. “”Our Ancestors the Gauls”: Archaeology, Ethnic Nationalism, and the Manipulation of Celtic Identity in Modern Europe.” American Anthropologist, New Series, 96, no. 3 (1994): 584-605. www.jstor.org/stable/682302.

Hansen, Leif, and Philipp Wolfgang Stockhammer. “October 2019 Rageot, M.* Et Al. P. W. Stockhammer*/C. Spiteri*, The Dynamics of Early Celtic Consumption Practices: a Case Study of the Pottery from the Heuneburg. PLoS ONE 14(10): e0222991.” (October 2019) PLoS ONE. Accessed November 14, 2019. https://www.academia.edu/40885806/2019_Rageot_M._et_al._P._W._Stockhammer_C._Spiteri_The_Dynamics_of_Early_Celtic_Consumption_Practices_a_Case_Study_of_the_pottery_from_the_Heuneburg._PLoS_ONE_14_10_e0222991.

Howego, Christopher. “The Monetization of Temperate Europe.” The Journal of Roman Studies 103 (2013): 16-45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43286778.

Julius Caesar, De Bello Gallicum

Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 89–102.

Murphy, Paul R. “Themes of Caesar’s “Gallic War”.” The Classical Journal 72, no. 3 (1977): 234-43. www.jstor.org/stable/3296899.

O’Hara, Charles Joseph. “Celts and Germans of the first century BC – second century AD: an old question, a modern synthesis.” Http://hdl.handle.net/, 2006, Http://hdl.handle.net/1842/29925.

Qizen, Xie. “The Ethnic Identity and Redefinition of the Galatians in the Hellenistic World.” University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository (May 2016), https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1284&context=honors

Sterm, Circe. Iron Age “Celts”: Ethnic and Cultural Identity. Accessed November 13, 2019. https://www.laits.utexas.edu/ironagecelts/ethnic.php.

Tacitus, Germania

Ursula Rothe. “The “Third Way”: Treveran Women’s Dress and the “Gallic Ensemble”.” American Journal of Archaeology 116, no. 2 (2012): 235-52. doi:10.3764/aja.116.2.0235.

[1] Dietler, Michael. Archaeologies of Colonialism Consumption, Entanglement, and Violence in Ancient Mediterranean France. Joan Palevsky Imprint in Classical Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

[2] Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 89–102.

[3] Caesar, Julius, De Bello Gallico

[4] Batinski, Emily E. “Lucan’s Catalogue of Caesar’s Troops: Paradox and Convention.” The Classical Journal 88, no. 1 (1992): 19-24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3297740.

[5] Caesar, Julius, De Bello Gallico

[6] O’Hara, Charles Joseph. “Celts and Germans of the first century BC – second century AD: an old question, a modern synthesis.” .

[7] Caesar, Julius, De Bello Gallico

[8] Sterm, Circe. Iron Age “Celts”: Ethnic and Cultural Identity. Accessed November 13, 2019.

[9] Caesar, Julius. De Bello Gallicum

[10] Caesar, Julius. De Bello Gallico

[11] Caesar, Julius. De Bello Gallico

[12] O’Hara, Charles Joseph. “Celts and Germans of the first century BC – second century AD: an old question, a modern synthesis.” Http://hdl.handle.net/, 2006, Http://hdl.handle.net/1842/29925.

[13] Caesar, Julius. De Bello Gallico

[14] Caesar, Julius. De Bello Gallico

Leave a comment