Written By Aaron Barnes, BA History

In By The Spear, Ian Worthington provides a secondary source on the exploits of King Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great. Worthington described King Philip II as the “architect” while Alexander the Great was the “master builder” of the Macedonian Empire. Worthington believes that Philip II is widely underestimated and overlooked due to his son’s fame and achievements. He argues that without Philip II there would be no Macedonian empire. He firstly provides the reader with analyses of Philip II’s rise to power, economic and military reforms, his military and political maneuvering in Macedonia, Illyria and Thrace, and the consolidation of the League of Corinth. Once Philip II’s contributions have been addressed, Worthington discusses Alexander the Greats conquests and legacy in Macedonia, Asia, and beyond. The main arguments posed by the book were that Without Philip, Alexander could not have attained his incredible feats. Also, that Alexander was a brilliant warrior, but in order to govern his empire he needed to adopt Persian customs of culture and governance, which distanced himself from his men.

Worthington goes on to compare and contrast the structure of the Persian Empire and Macedonian Empire with Greek empires of their time; centralized power with satraps who involve local populaces when applicable, versus a loose confederation of tribute giving states. He argues that the Persian and Macedonian model of empire building was more stable than Greek hegemony or the Athenian Empires. For example, in Thessaly and other territories, King Philip II placed personally appointed governors that answered only to him in charge of the regions; similar to a satrapy (Worthington 75). Also, Philips “Common Peace” made it so Greek city-states would swear a personal allegiance to Philip and his descendants, and if a city-state broke the agreements, a coalition of Macedonians and Greeks would descend upon the aggressor’s city (Worthington 100). The critique provided against the Athenian Empire was that at the time, they were so loosely under control that the factions were free to make treaties or alliances with other nations (Worthington 76). The following chapters are dedicated to Alexander III, better known as the Great. In order to look through the lenses of Hellenization and empire building, Worthington really wants the readers to understand the cultural differences between Macedonians and Greeks before discussing the events that changed Greek history. This is due to their stronger centralized government, polygamy and their masculine, war-like tendencies. Worthington hints that these are main reasons for their successes in empire building, by conquest and marriage. Although they share a similar language and pantheon, Macedonians are heavy drinking, monarchical, and their kings are expected to be fierce and masculine warriors; Worthington uses speeches from Demosthenes and other Greek statesmen to explain how the Macedonians were viewed as part barbarian, part Hellene. Early on in the book, Worthington attempts to separate Alexander from myth and legend; since primary sources at the time are very scarce, many other historians hundreds of years later are the closest sources we have to the timeline. Among a few other myths or Alexander’s conception and promise, he mentions myths regarding the taming of Bucephalus (Ox-Head) and Philip II’s visions of his wife making love to a snake who represents Zeus, thus being the father of Alexander. Next, Worthington discusses Alexander’s early kingship, numerous revolts and the immense battle experience beginning with the battle of Chaeronea when Alexander III was only eighteen years old and led a pivotal charge against the fearsome Sacred Band of Thebes. The rest of the book mentions Alexander’s push into Asia Minor and his campaign into Egypt; this is where Worthington pivots the tone of the book to be less battle oriented, and more concerned with Alexander’s shifting personality and the morale of his men. This is due to the fact that when in Siwa, Alexander received what he interpreted as confirmation of his divine heritage from an Egyptian high priest. From this point on, Worthington mentions instances where the moral of his men is tested by Alexander’s attitude that King Philip II was only his “mortal father” and Alexander’s insatiable thirst for conquest.

Worthington argues that Alexander’s shifting personality negatively affected the morale of his generals and Macedonian soldiers due to their fierce nationalism. As the campaign through the once expansive Achaemenid Empire continued to result in victory, Worthington reflects on the orientalization of Alexander the Great. Worthington discusses mass marriages of Alexander’s men to Persian nobility (most not lasting upon his death, with the exception of Seleucus), his own matter of dress and adoption of Persian custom, and his marriages to eastern women. Many Greeks, including Aristotle himself, believed that they were superior to Persians and had the right and obligation to treat them as “plants and animals” while subjugating them under Greek rule (Worthington 56).

Finally, the book ends with Alexander’s death in Babylon; his future plans to invade Arabia and later the Western Mediterranean were never realized due to the factions of successor states which divided up his empire and fought amongst themselves. While short lived, Alexander the Great’s empire ushered in a new era of Hellenic history while ending classical Greek history and had lasting effects on the ripple of time.

By The Spear raised many erudite observations and arguments about Philip II and Alexander the Great, most were backed by fact and source; but some observations seemed to have either misconstrued evidence or contradicted what I have learned in lecture. Worthington discusses the assassination of Philip II in great detail, goading at the presence of a conspiracy by saying, “How Pausinius killed Philip is certain enough. Why he did so is a different matter because ancient accounts offer conflicting motives (Worthington 113).” According to Worthington’s deduction from his primary sources, Pausinius was a scorned lover of Philip’s.

“Philip had ended a homoerotic relationship with him and taken up with another man. This personal motive is at odds, however, with statements by Plutarch, that it was “Olympias who was chiefly to blame for the assassination, because she was believed to have encouraged the young man… Pausinius was certainly a jilted lover, but Philip had ended their affair some time ago (Worthington 113).”

This assessment conflicts with the lecture provided by Jeremy LaBuff, PH.D at Northern Arizona University, where the class were told that Pausinius was raped and dishonored. According to notes from Dr. Jeremy LaBuff, Pausinius was raped by a number of Attalus’ men. When Pausinius confronted Philip II seeking justice, Philip instead promoted Pausinius and told him to forget the incident, since Attalus was pivotal to lead the Asian invasion. The lecture goes on to say that Pausinius killed Philip II and Attalus in the arena the day of the assassination. Attalus was actually killed by Parmenion in Asia minor connected to a plot to assassinate Alexander III coordinated by Demosthenes. Therefore, the class deduced that Pausinius killed Philip II out of dishonor rather than a crime of passion. Another conflicting passage from the book and the lecture regards Philip’s burial site. The date for the discovery of Philip’s tomb is 1981, where Worthington cites 1977 as the date. Secondly, the lecture assumes that the twenty or so year old woman buried with who is presumably Philip II as his last wife, Cleopatra, but Worthington cites that is may have been his sixth wife, Meda of the Getae. The Dacian Getae were a warrior society whose women may have practiced ritual suicide with the death of their husbands; therefore, Worthington believes she is the wife buried in the tomb (Worthington 124-5).

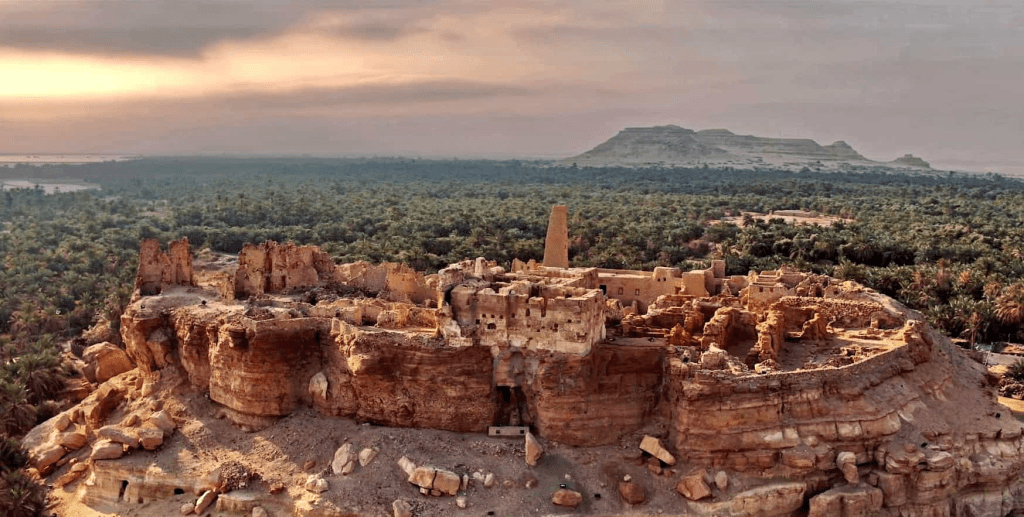

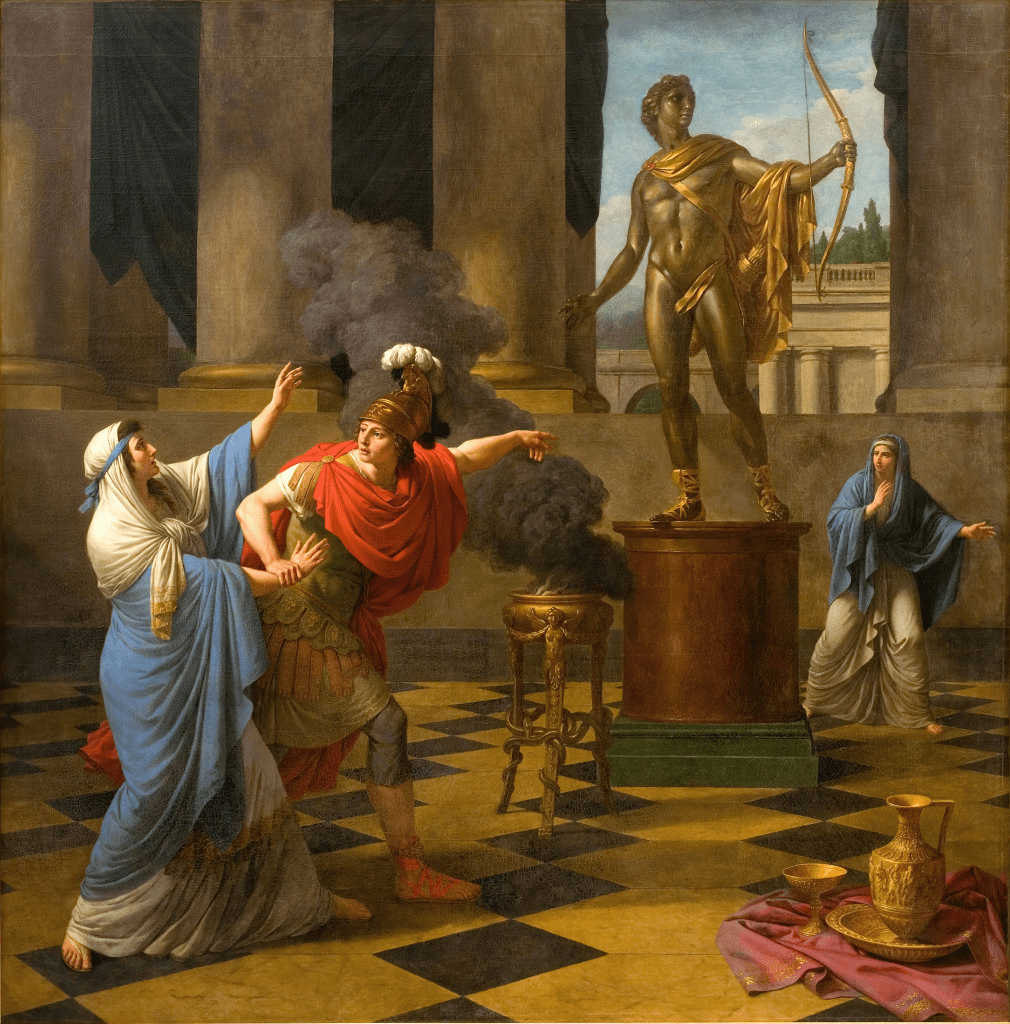

Worthington mentions the piety of Alexander the Great and how he always pays respects to the gods, tombs of heroes and to his ancestors, evidence of his piety arises all throughout his campaign in Asia and in Greece as well. Although at face value these may be acts of piety, many of these actions can be viewed as having ulterior motives. For example, at the Hellespont and in Troy (at this time it was called Hisarlik), Alexander poured libations to the nymphs of the sea, sacrificed at the tomb of Achilles (a maternal ancestor) and Ajax. Hephaestion ran naked around the tomb to evoke the funeral games made for Patroclus; Alexander also sacrificed to Priam to appease the spirit of the dead king. Finally, in the temple of Athena at Troy, it was believed that the arms of Achilles were hung up there; at this moment, Alexander swapped his shields for Achilles’ in order to identify himself with the Homeric Hero (Worthington 141). Later in Egypt, Alexander receives a message from a high priest to Zeus Ammon which he interpreted to mean that he is the son of Zeus (the priest may have said O paidion, meaning “my boy”not O pai Dios, meaning son of Zeus), making him a demi-god.

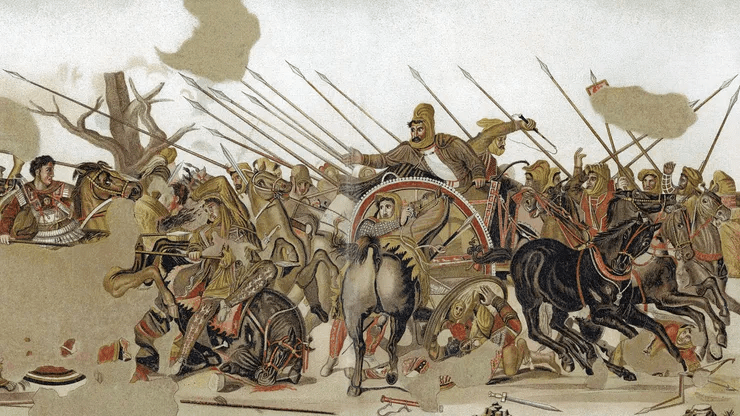

When instances of Alexander arise that equate him to Homeric heroes or even the gods, it makes me believe that his piety could have been a cultural and contemporary way to gain influence or power over his subjects and soldiers. It raises the question, was Alexander truly a devoutly religious man, a tactful leader using religious themes to solidify his power or was he a megalomaniac? Perhaps he could have been a mixture of all three of these possibilities. Ptolemy himself later asserted that in Egypt, Alexander “heard what he found agreeable to his desires” (Worthington 183). An instance that raises the integrity of his devoutness is his treatment of the Oracle at Delphi. Alexander was denied entry due to the Oracle’s inability to offer prophecies during winter time, so Alexander barged in and physically forced her to offer him a prophecy. Whether it was a legitimate prophecy or something that the Oracle crassly told Alexander due to his harshness, she told him that he was invincible. This further added to Alexander’s ego and influence, since he was so favored by the gods. Perhaps this is the reason why Alexander insisted upon leading from the front and placing himself in precarious positions like at the Battle of Granicus.

It is without a doubt that Alexander the Great was a ferocious warrior and genius in the art of warfare as he demonstrated in his countless sieges, battles and victories. His victory at Issus was the most decisive battle of his campaign, now he was in control of the majority of the Persian Empire. Like in Egypt, Alexander the Great was accepted as a liberator from tyranny, and welcomed into the city with open arms. After the battle of Issus Alexander and his men rested in Babylon for a month enjoying fine wines and countless courtesans and prostitutes. It was here where Alexander began to adopt Persian dress, custom, and wives and here he appointed his first non-Greek satrap. Diodorus informed us that Alexander began to wear select items of Persian clothing,

“a white robe and girdle, and the purple and white headband that Darius had preferred. Probably because he now received one of the royal titles, ‘king of lands’ ”(Worthington 195).

To his men, Alexander was beginning to look more like the conquered than the conqueror. According to Dr. Jeremy LaBuff, Alexander even went so far as to accept subjects laying in proskynesis before him, an action Greeks kept for the gods. To add even more insult, Alexander the Great appointed Mazaeus as satrap of Babylonia, this is the enemy general at Issus who nearly killed Parmenion. N.G. Hammond equates creates a comparison using World War II as an example; “If King George VI had appointed Rommel after the Battle of El Alamein to be his Viceroy of India”. This is a fair equivalency and it is fair to see how the Macedonians would be disgruntled with this action.

On one hand Alexander embraced aspects of Persian culture; but on the other, he burned Persepolis to the ground after allowing his men a full day of plundering and rape. Alexander the Great was a very dynamic character and his mentality is hard to grasp, especially with the primary sources being either biased or not exactly contemporary. I digress, eventually Alexander’s actions led to a mutiny in India and to a suspicious death in Babylon.

Worthington’s most used primary sources for his book come from Plutarch, Diodorus, Ptolemy and Callisthenes. Out of these four sources, only the later two are contemporaries of Alexander the Great. Ptolemy was a childhood friend of Alexander’s and a high ranking officer who eventually founded the Ptolemaic Dynasty in Egypt. Callisthenes was Aristotle’s great-nephew, who was appointed as being Alexander the Great’s biographer and historian. While both have Greek or Macedonian bias and both were on campaign with Alexander, Ptolemy should be regarded as the lesser of the biased contemporaries. Callisthenes was essentially there to document Alexander’s achievements, embellish them, and send his reports back to Greece in order to garner support. For all intents and purposes, he was a creator of propaganda. On the other hand, Ptolemy was a general fighting alongside Alexander, he even criticized Alexander’s behavior after visiting the shrine of Zeus Ammon. This critical comment of Alexander proved that he was not entirely bound by duty to make his superior look god-like, like Callisthenes. Worthington is consistent and fair in his analysis of his sources, unfortunately Alexander the Great does not have a very wide selection of contemporary primary sources.

Worthington spends much of the chapter: The Downfall of Greece, he refutes much of the mysticism surrounding Alexander the Great trying to portray him as he actually was. Worthington even discusses how some sources depict Alexander as being short, blonde and perceived as ugly by saying “at Susa when he sat in the throne his feet did not touch the ground”. This contrasts the heroic dark haired and manly image people like the Romans peddled. Also throughout the book when discussing battle figures provided by Callisthenes, he almost always mentions that they were more than likely exaggerated in order to seem more glorious, this is something common in ancient historian accounts as we have discussed in lecture and seen in Herodotus.

Ptolemy often praised or critiqued Alexander based on his own opinion rather than with a mission, but when talking about other generals or officers, Ptolemy was overly critical and biased. The officers in Alexander’s inner circle were highly competitive and jealous of one another, specifically Hephaistion. After Alexander’s death the successor states of his empire, especially Seleucia and Ptolemaic Egypt fought wars with one another; therefore, he does not provide an unbiased account of certain aspects within the Macedonian Empire.

Plutarch and Diodorus lived during the reign of the Roman Empire and Roman Late Republic in Roman-controlled “Greek” territory. They did their analysis on Alexander the Great through the use of stories, legends and primary sources that we still use today. They wrote their accounts hundreds of years after Alexander the Great’s conquests through a lens of Roman and late Hellenic culture. These two cultures had leaders who essentially wanted to emulate Alexander the Great, making him seem much more spectacular and legendary than he was as a mortal human being.

With these different sources in mind, it is a travesty that there are no surviving Persian sources or other sources other than Hellenic/Hellenistic for that matter, available to us to avoid bias. One can piece together enough of the truth by reading all of the different sources provided by different historians or contemporaries, but reading between the lines of one side only gets so far. If there were Persian sources available to historians, a much clearer image of Alexander the Great’s conquest and governance would be a real possibility.

When considering alternate viewpoints to Worthington’s views on Philip II and Alexander, the task becomes difficult since Worthington does not seem to offer many, if any, opposing viewpoints. He will simply state his opinion, use evidence from his previous books or research, then move along without contesting anybody. Although the section regarding Philip’s death did seem to be the area of most controversy during my readings. Worthington seemed fairly confident that Olympias was the one pulling the strings and used loose evidence to implicate Alexander as well. He used Alexander’s question to the Egyptian priest, “have all my father’s assassins been punished?” and the fact that alexander asked that question 16 years later, as evidence that Alexander was seeking forgiveness or clearance from the gods. According to Dr. LaBuff, the Hellenist at Northern Arizona University, Philip was killed under much more transparent means. I find it strange that the evidence or explanation provided by these two experts had little common ground save the assassin’s name.

Bibliography

Worthington, Ian. By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Hammond, N. G. L. The Genius of Alexander the Great. Duckworth, 2004.

LaBuff, Jeremy PH.D, 2018, Alexander the Great’s Empire, [Power Point Slides], College of Arts and Letters, Northern Arizona University.

Leave a comment