Written By Aaron Barnes

Introduction

In 1801 a lord from Scotland, Thomas Bruce, arrived in Athens to seek permission to cast and sketch the marble statues on the Acropolis. After some political maneuvering, the Lord began to take the statues themselves back to England over an eleven year period. Today they reside in the British Museum in London, separated from their birthplace in the temples of the Acropolis in Athens. The question asked by the international community is: should the Elgin Marbles be returned to the Parthenon, the place of their origin, or remain in the British Museum in London? Based on the arguments presented by both sides, I will argue that the Elgin Marbles should be returned to Athens. In order to best comprehend the influences, nuances and importance of this debate, we must examine three main points: the history of how the Marbles were appropriated, the debate over the legality, and the morality.

History of the Marbles and their Appropriation

The Parthenon Marbles, also known as the Elgin Marbles, are a collection of marble statues and carvings taken from different temples on the Acropolis in Athens. They were taken to England by Thomas Bruce, the 7th Lord of Elgin, from 1801 to 1812. Thomas Bruce was an ambassador during the reign of King George III, and became tasked with negotiations with Ottoman Empire’s emissaries and dignitaries in Greece. The Marbles depict Greek mythology, and were commissioned by Pericles, and created by Phidias and his assistants in the mid 5th century B.C. During the creation of these works, Athens experienced its golden age of empire; this followed the Greek victory during the 2nd Persian War. Due to Athenian hegemony, this time period was fraught with cultural intrigue and philosophical works. During this time period, Athenian democracy and philosophy are most well-known.

The marbles and Parthenon went through a few distinct periods of history that caused significant damage to the site prior to Bruces’ arrival in Greece. Unfortunately, throughout history, the Marbles were not protected or kept in pristine condition. Firstly, when Greece converted to Christianity during the reigns of Emperors Julian and Constantius II, the Parthenon was turned into a church and many of the pagan sculptures were destroyed, looted, or repurposed. Secondly, during the Ottoman capture of Athens in 1453 A.D., the site was converted into a mosque, areas were destroyed and repurposed as well. Next, during the Great Turkish Wars of the 17th century, the Republic of Venice in particular bombed the Parthenon to smithereens; since it was repurposed, yet again, to be an Ottoman munitions store. Finally, by the time Bruce arrived, the Ottomans had kept the nearly ruined Parthenon as a military base, where the lime was being repurposed by citizens and the statues used as target practice by troops.[1]

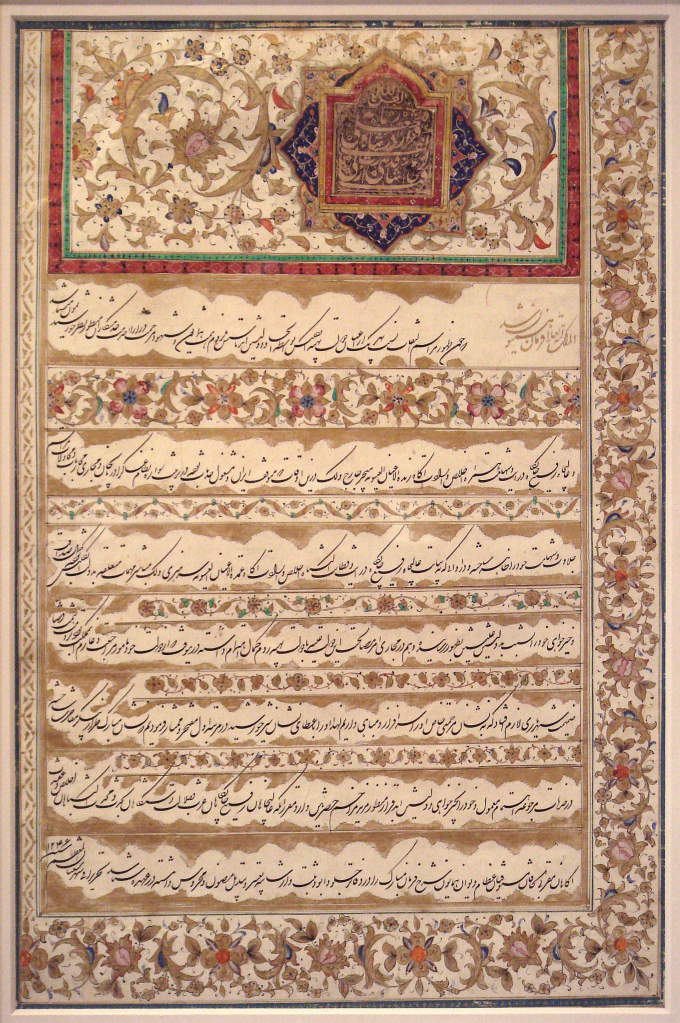

The form of procurement by which Bruce was able to obtain the Marbles is contentious and scandalous. The Lord of Elgin supposedly appealed to Ottoman bureaucrats of the Sultan’s office to seek permission to use European artists to cast and sketch the Parthenon; the Sultan’s response was initially negative according to Bruce’s own accounts. Then Bruce employed local artists and at this point the Sultan gave him permission. I say this as “supposedly” because there is much controversy around the legitimacy of his document.[2] “He (Bruce) stated that he had obtained a firman (a royal decree issued by the Sultan’s office) from the Sultan which allowed his artists to access the site, but he was unable to produce the original documentation. However, Elgin presented a document claimed to be an English translation of an Italian copy made at the time. This document is now kept in the British Museum. Its authenticity has been questioned, as it lacked the formalities characterizing edicts from the Sultan. Vassilis Demetriades, Professor of Turkish Studies at the University of Crete, has argued that

“any expert in Ottoman diplomatic language can easily ascertain that the original of the document which has survived was not a firman.”[3]

This suggests that Bruce may have forged his own document in order to circumvent the initial block by the Sultan’s office.

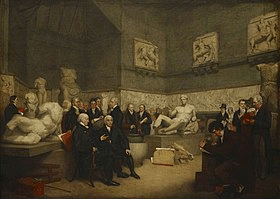

Bevan argues that architecture and culture are connected; therefore, the removal of these artifacts from their original place is damaging to the Greek culture. The Marbles were relocated to U.K. at a personal expense to Lord Elgin of about 70,000 British pounds to originally decorate his manor in Scotland. Even in the 19th century when he finally procured these relicts, his country debated the issue. Some praised him and others condemned his acts. However, due to a divorce settlement, he sold the Marbles to the British museum for 35,000 pounds in 1812. He declined much more significant offers from foreign nationals including Napoleon himself. Now in modernity, the marbles have remained in London for about 200 years. Now that the historical context has been explained, we can frame the arguments around the legality and morality of the Elgin Marbles controversy.

Legality Regarding Procurement

The legality of this issue is clouded since the transaction between the Ottoman government and Elgin was shaky. The controversy surrounding the “firman” is inconclusive and hundreds of years old and involves a government that no longer exists. However, according to Tristram Hunt, the director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, the reason that the Greeks have not brought this matter to court, is that they know they would lose[4].

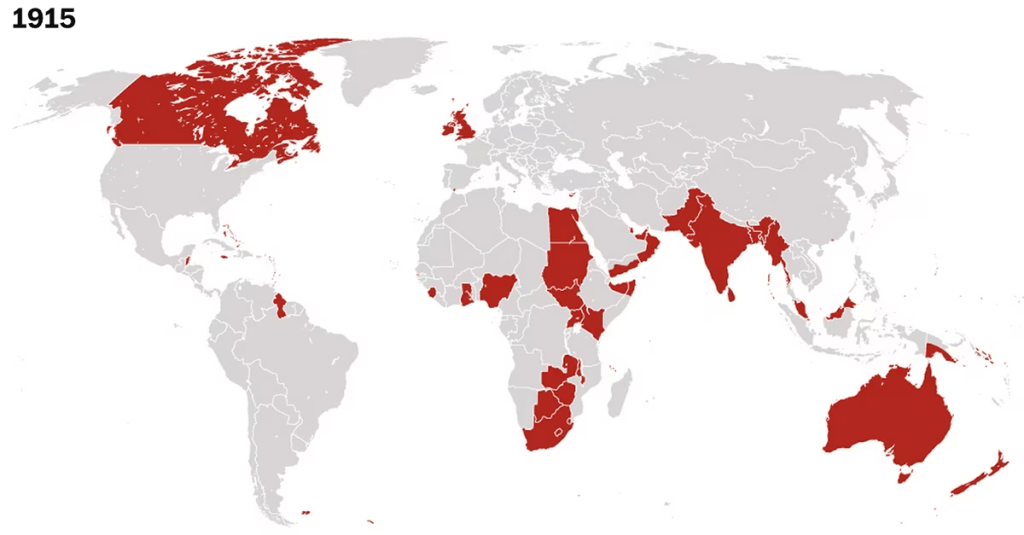

I believe that it is important to remember that during this time period, Great Britain was at the peak of its empire, the Ottoman Empire held great influence and territory, and that Greece had not been a united sovereign state ever before in its history. Some Lords hailed Bruce as the savior to the Marbles, while others, such as Lord Byron, considered it a theft. Lord Byron was a British Lord who became an outspoken supporter for the new Hellenic Republic who died in Greece and loudly criticized Elgin’s appropriation of the Marbles. This draws a connection between the national identity of a newly formed state with cultural monuments from the past and a same geographic location. The late John Henry Merryman, a world-renowned lawyer in matters of cultural property and art, wrote a journal arguing the legality of the matter in favor of the British Museum. He cited the signed document from the Ottoman Sultan as well as cited the 1954 Looting Act to counter arguments put forth for repatriation of the Marbles. Opponents like Andrew George, often cite the act as a violation of the 1954 legislation, but the act does not protect looting prior to its passing[5]. Over history many empires have looted art and relicts from foreign nations. The caution of setting a legal precedent frightens many of these nations whose cultural heritage was once empire.

Setting a legal precedent that makes most western museum collections vulnerable to repatriation of artifacts is a major concern of those who oppose shipping the marbles back to Athens. During a debate on the issue hosted by, Intelligence2, Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, a History professor emritus of Notre Dame, exclaimed,

“Academics do not believe in precedent per se, but the courts do!”

To which Tristram Hunt, director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, followed up,

“the removal of these (Marbles) will set a precedent to empty cosmopolitan museums everywhere.[6]“

This is something that the English should be aware of when deciding to carry on with Greece’s demands. Participants in the debate asked what would happen to the Louvre, the Benin Bronzes, the Rosetta Stone, the Busts of Nefertiti? The list of artifacts goes on. In order to rebuke this accusation of theft, museums in the UK, specifically the British Museum allow “long-term loans” to the countries of origins for their artifacts.[7] This does well for public relations for the museum and allows certain artifacts to go back to their countries of origin or around the world; however, this is not permanent and is reliant upon the good graces of the museum itself. This debate certainly sheds light on the deeper yet broader issue of how formerly imperialist nations can deal with their past; and how their subject nations can heal from cultural genocide or define their own heritage away from the scope of being a subject nation. Supporters of the movement like Stephen Fry constantly say “how classy” it would be for the U.K. to send these artifacts back to show the world they are willing to pay reasonable penance for their past. Opponents however, like the prime minister Boris Johnson, say, “Britannia did not rule the waves wearing floaties”, meaning that history is harsh and the reason for their world domination was that they were willing to be tough.

To counter this seemingly compelling argument of legal precedent, some argue about the specificity of this controversy. Andrew George, a U.K. Labour Party leader, argued against this sentiment in the Intelligence2 debate. He said that,

“things of this nature are dealt with in a very particular case by case basis and it would not cause a precedent of emptying museums”.[8]

The Marbles and other artifacts have very specific histories, historiographies, circumstances, characteristics, etc. creates trouble in establishing a structured legal precedent for cases like this. The issue of legality is only a part of the puzzle in this debate. Morality and ethics are also major factors; in fact, they are mentioned more frequently than the legality of the Marbles in general.

Arguments Regarding Morality

Morality, cultural heritage and modern politics all find themselves as part of the debate about the Elgin Marbles. Greece is not the same country from antiquity and has never been a united country until the formation of the Hellenic Republic in the 1860’s. Also, Great Britain, had committed countless atrocities and stole countless artifacts as an empire. Therefore, does modern Greece truly have a valid claim to these statues and does the U.K. have an obligation to atone for their imperial past?

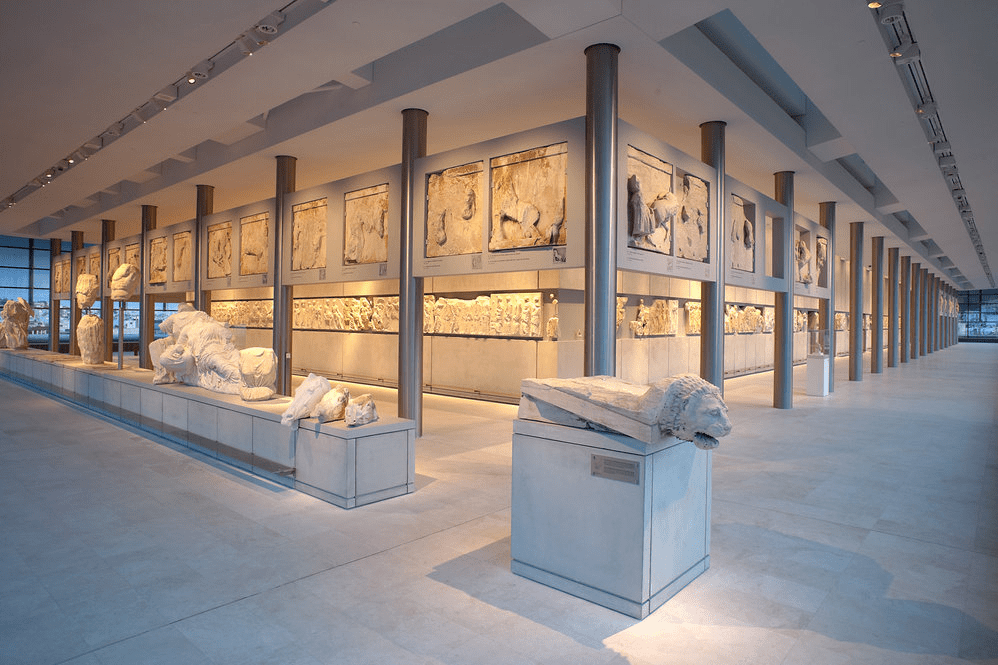

According to polling data provided by mainstream media outlets in the U.K. as well as demonstrated in the Intelligence2 debate, a slim majority of U.K. citizens are in favor of returning the Marbles back to Athens. [9] In fact, prior to the Intelligence2 debate, 196 of the attendees voted for the return, while 202 voted against the return; 158 remained unsure. After the debate, however, 384 attendees voted for the return, 125 against, and 24 remained unsure. [10] According to a poll done by The Independent UK, normal people in the U.K. and Greece generally want the marbles returned to Athens. Of the participating audience members at the debate, some attendees thought that the current museum exhibit is a disservice to the Marbles. People equated the architecture of the exhibit as cold and similar to an airport terminal. Others complained about the fluorescent and artificial lighting. Some members English audience members thought that it was a travesty to keep a whole piece of art separated rather than with the other sculptures and engravings; which tell a whole story as they were intended to do. Greek nationals in attendance at the debate were asked to give their opinions. One Greek said that to not have the Marbles united is akin to having a family photo with some of your family missing. Another said that if the marbles were returned, Greeks would forget all about the debt crisis and rally together with pride. This demonstrates Bevan’s point on the importance of culture to a nation and how the removal or “erasure” of these statues affects the mentality of thousands of people. However, one Greek man supported them staying in London. He said that the Parthenon finally became restored only about 50 years ago, but now when you go up to the Acropolis, the site is defaced thoroughly with vandalism. Therefore, Greek law enforcement cannot handle more artifacts and that they should remain in London. The final comment from the audience was given by a young Englishman; he said that, “with technology it is possible to cast these sculptures and essentially make identical copies. Why not do that, then send the statues back to the Greeks. As an Englishman I would rather have friends in Greece and copies here!”.

Tristram Hunt and the supporters who oppose the movement believe that not only is the British Museum the safest place for them, but that their position is in a place of honor that will be seen by many more people than if they were sent to Athens. Hunt as well as Hartwig Fischer, the director of the British Museum, vehemently believe that the Greeks should,

“have a sense of pride and honor that these monuments are housed in one of the three top museums of the world.”

On the other hand, people like Stephen Fry equate this whole ordeal to Nazi occupied Netherlands. He said that it is not too far of a stretch to imagine the Marbles as a Rembrandt, and Lord Elgin as an American ambassador signing a writ of sale with a Nazi official for a piece of Dutch art.

Finally, this leads us to an important question; is Athenian history and culture, Western culture in general? And does returning these Marbles take Europe away from cosmopolitanism and back toward nationalism? Many westerners identify their history with the history of ancient Rome and Greece in modernity. The concepts of democracy and equality (for male citizens at least) in Golden Age Athens finds itself in many constitutions in European countries and the United States. Additionally, the E.U. emphasizes its cosmopolitan attitude and unity of nations. Opponents of the movement, like Tristam Hunt, use this sentiment as an argument against the return of the Marbles. For example, Hunt and others emphasize the fact that Greece has only started this process of repatriation in the last 50 years, around the same time that they started to restore the Parthenon[11]. Using this as evidence, opponents say that this is not a matter of history or culture, but a matter of a renewed nationalistic movement by the Greeks. On the other hand, Stephen Fry and other supporters of the movement, speak on the history and culture of Greece and tie it in with their debt. In the Intelligence2 debate, Fry said that,

“we should not have disdain for the economic conditions in Greece or for their debts. For they have provided us with something far more valuable, and it is in fact, us who owe a debt to them!”[12]

The unity and amiability that could be achieved by sending the Marbles back, or at least giving them to Greece on a long-term loan until they prove how they would treat the artifacts, seems like a more than fair trade that speaks to the values of the U.K., the E.U., and Greece.

My Conclusion

Over the last 50 years the contention between those who support the repatriation of the Marbles and those who oppose it has picked up pace. Especially with the discussion of Brexit and the signs of revivalist nationalist movements in Europe[13], people with influence, as well as the common people, have thought about the Elgin Marbles in a renewed light. The history of the Marbles set them in Greece for millennia, until the British may have saved them from complete destruction. Greece is now in a relatively stable condition and the Parthenon is being restored more every year. Greece is ready to have the Marbles reunited with the rest of the artwork on the Acropolis. Although the legality of the purchase of the Marbles is questionable, it has not been tried in court and likely will not be due to the nature of the case. Despite several legal experts saying Greece has no legal claim, other experts could be called into court to dispute the authenticity of the documents effectively. Keeping this out of court would be the best choice to avoid a legal precedent being set; therefore, they should just be returned in good grace, as to avoid litigation. Finally, the morality of the matter stands more in favor of the people of Athens. Most English people themselves even support the return of these artifacts.

In conclusion, when we consider the history, legality and morality of this issue, the most sensible choice seems to be that the Marbles belong together, united on the Acropolis in the temple of Athena-Nike and Poseidon, where they stood originally in 450 BC. The west owes much to the legacy of ancient Greece, let their modern counterparts have their statues, once they Marbles are united, so too will the relationship between the U.K. and Greece grow stronger.

Bibliography

Selwood, Dominic. “How Brexit Has Revived Controversy over the Elgin Marbles in Britain.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 14 Sept. 2018, www.independent.co.uk/news/long_reads/elgin-marbles-parthenon-sculptures-ancient-greece-british-museum-brexit-a8520406.html.

“Send Them Back: The Parthenon Marbles Should Be Returned to Athens.” Intelligence Squared, www.intelligencesquared.com/events/parthenon-marbles/.

Cook, B. F., British Museum, and British Library. The Elgin Marbles. London: Published for the Trustees of the British Museum by British Museum Publications, 1984.

Damien McElroy, Foreign Affairs Correspondent. “British Museum under Pressure to Give up Leading Treasures.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 7 Apr.2010. www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/egypt/7563963/British-Museum-under-pressure-to-give-up-leading-treasures.html.

Demetriades, Vassillis. Was the removal illegal?, September 1997. http://www.parthenon.newmentor.net/illegal.htm.

Livingstone, Josephine. “The British Museum’s ‘Looting’ Problem.” The New Republic, 14 Aug. 2018, www.newrepublic.com/article/150642/british-museums-looting-problem.

Merryman, John Henry. “Thinking about the Elgin Marbles.” Michigan Law Review 83, no. 8 (1985): 1881-923. Rea, Naomi. “The British Museum Says It Will Never Return the Elgin Marbles, Defending Their Removal as a ‘Creative Act’.” Artnet News, Artnet News, 28 Jan. 2019, news.artnet.com/art-world/british-museum-wont-ret

[1] Selwood, Dominic. “How Brexit Has Revived Controversy over the Elgin Marbles in Britain.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 14 Sept. 2018, www.independent.co.uk/news/long_reads/elgin-marbles-parthenon-sculptures-ancient-greece-british-museum-brexit-a8520406.html.

[2] Merryman, John Henry. “Thinking about the Elgin Marbles.” Michigan Law Review 83, no. 8 (1985): 1881-923. 30

[3] Demetriades, Vassillis. Was the removal illegal?, September 1997. http://www.parthenon.newmentor.net/illegal.htm.

[4] “Send Them Back: The Parthenon Marbles Should Be Returned to Athens.” Intelligence Squared, http://www.intelligencesquared.com/events/parthenon-marbles/.

[5] Merryman, John Henry. “Thinking about the Elgin Marbles.” Michigan Law Review 83, no. 8 (1985): 1881-923. 3

[6] “Send Them Back: The Parthenon Marbles Should Be Returned to Athens.” Intelligence Squared, http://www.intelligencesquared.com/events/parthenon-marbles/.

[7] Livingstone, Josephine. “The British Museum’s ‘Looting’ Problem.” The New Republic, 14 Aug. 2018, http://www.newrepublic.com/article/150642/british-museums-looting-problem.

[8] “Send Them Back: The Parthenon Marbles Should Be Returned to Athens.” Intelligence Squared, http://www.intelligencesquared.com/events/parthenon-marbles/.

[9] Livingstone, Josephine. “The British Museum’s ‘Looting’ Problem.” The New Republic, 14 Aug. 2018, http://www.newrepublic.com/article/150642/british-museums-looting-problem.

[10] “Send Them Back: The Parthenon Marbles Should Be Returned to Athens.” Intelligence Squared, http://www.intelligencesquared.com/events/parthenon-marbles/.

[11] “Send Them Back: The Parthenon Marbles Should Be Returned to Athens.” Intelligence Squared, http://www.intelligencesquared.com/events/parthenon-marbles/.

[12] “Send Them Back: The Parthenon Marbles Should Be Returned to Athens.” Intelligence Squared, http://www.intelligencesquared.com/events/parthenon-marbles/.

[13] Selwood, Dominic. “How Brexit Has Revived Controversy over the Elgin Marbles in Britain.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 14 Sept. 2018, www.independent.co.uk/news/long_reads/elgin-marbles-parthenon-sculptures-ancient-greece-british-museum-brexit-a8520406.html

Leave a comment