Introduction

The Hellenistic Era is commonly known as the period in between Alexander the Great’s death and the establishment of the Roman Empire. During this period in history the ancient Mediterranean experienced a string of technological advancements and successor kingdoms who engaged in an unprecedented naval arms race. I will be using knowledge from lecture by Jeremy LaBuff, PH.D, independent research, as well as my most recent reading listed below.

Secondary Source

In The Age of Titans: The Rise and Fall of the Great Hellenistic Navies, by William M. Murray, the reader is given historical and archaeological evidence that explains the reasons behind the construction of such grandeur ships. The chapters of the book discussed Classical Greek warfare, new technologies, Philip and Alexander’s conquests, early Diodochi conflicts, later Diodochi conflicts, types of ships used in both, the Ptolemaic grand fleet, and finally the end of the “big ship era”. Each of these chapters provides insight into the phenomenon that culminated in engineering marvels and exciting, impactful conflicts. The book had a handful of main arguments and themes that Murray seemed to have wanted to make clear to the reader. He came to his conclusions using factual evidence, and used alternate viewpoints from author historians to attempt to refute their arguments by analyzing the same sources.

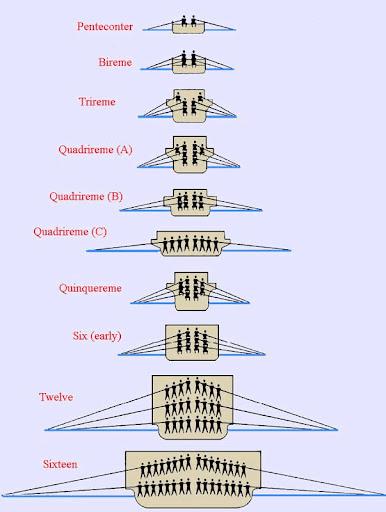

In chapter one and two, the chapters regard the development of “fours” and “fives”, or quadrireme and quinquereme, as well as frontal ramming tactics. Murray uses instances of battles and cites old naval tactics to argue that battle tactics and objectives have changed since the Classical era. In the western Mediterranean, Murray discusses Dionysius I of Syracuse and the war with Athens, known as the Athenian Expedition, marked an era of new naval warfare. By relying more on missiles, fighting in confined spaces rather than open sea, and by using a fleet in conjunction with an army during a siege, this conflict displayed innovation not seen in the classical period. As Murray states,

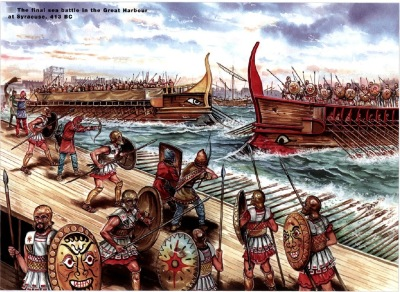

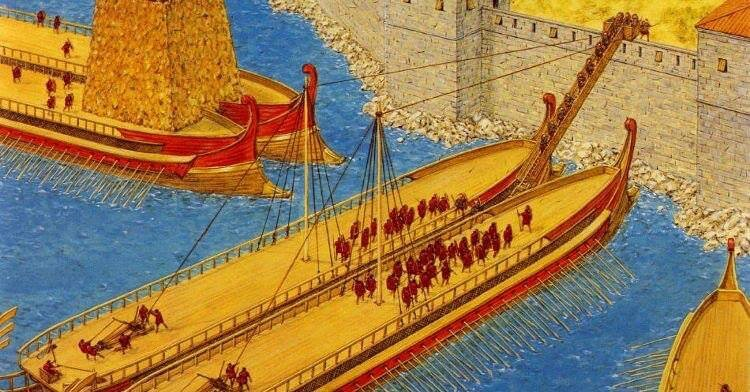

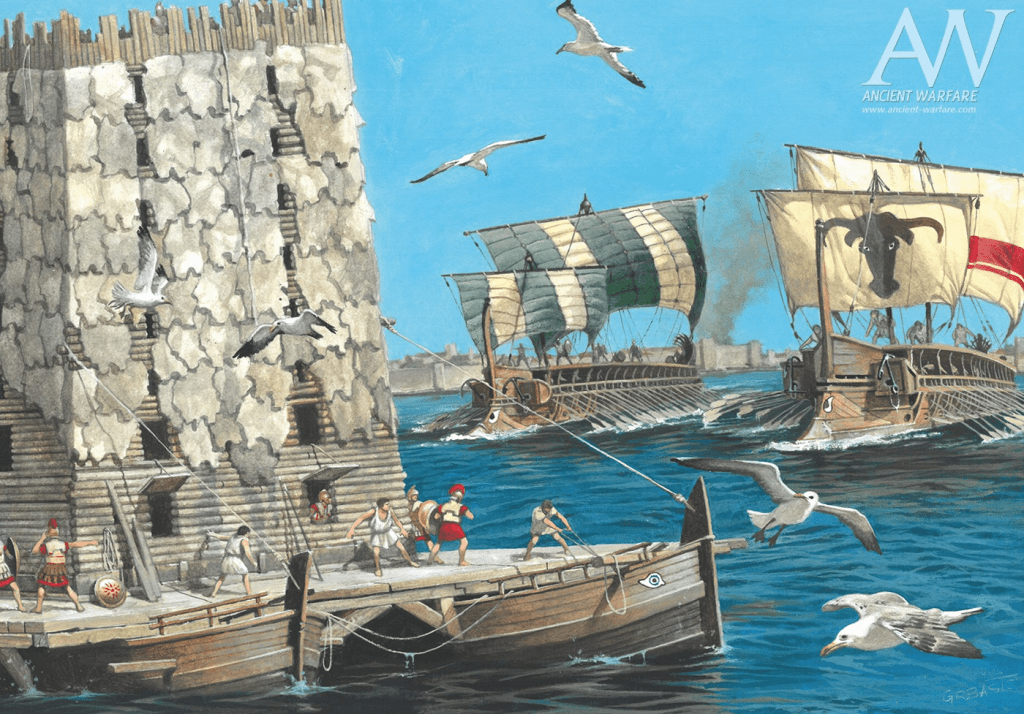

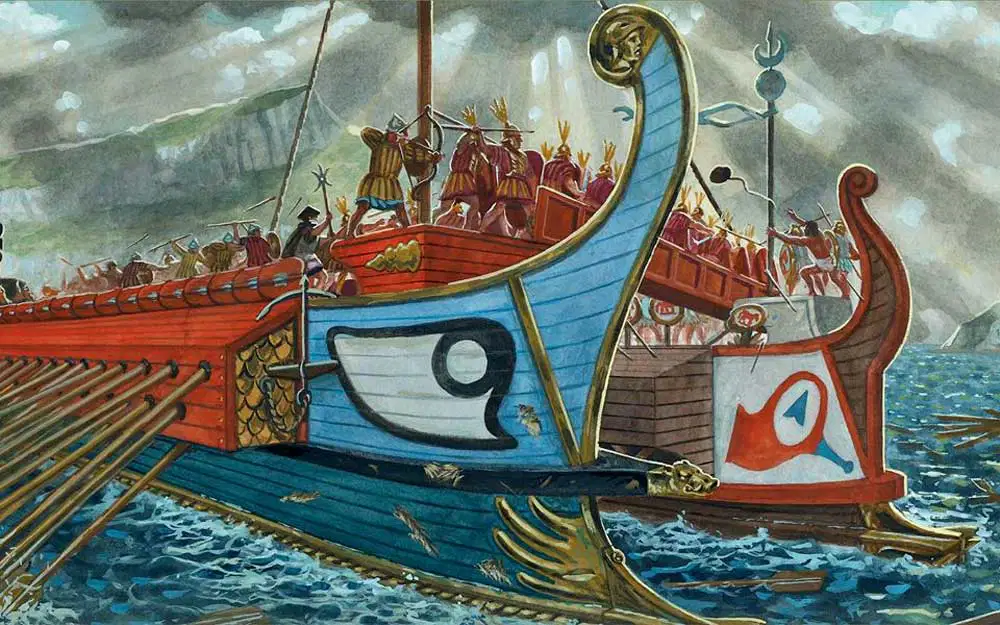

“By 413 BC, we see the essential elements that come to dominate Hellenistic Naval Warfare: frontal ramming attacks, the discharge of long range projectiles, and the use of small boats to slip in between the ships in the enemy line. [These tactics were best utilized while Athens and Syracuse fought in the opening of the Syracusan harbor.] [ The Syracusan navy used flaming projectiles and set ablaze an old cargo ship in order to send downwind to the Athenian fleet station. They also linked together vessels at the mouth of the harbor in order to restrict an Athenian retreat].” (Murray 22-23).

Murray writes about the Siege of Syracuse and how it was mainly fought in the harbor of the city-state; therefore, the Syracusans obtained the advantage of being able to create defensive measures. Syracuse trapped the Athenian navy in the harbor by using a zeugma or a pontoon barrier; this tactic became common in the Hellenistic era as a form of defense. Syracusan ships laced together by timbers or rope in order to create a blockade out of the harbor would hinder the movement of the highly-mobile triremes leaving them open to attack, which is exactly what happened to the Athenian fleet. The Syracusans peppered the Athenian fleet with arrows, sling stones and javelins, ultimately defeating one of the strongest navies of the era by using unconventional tactics.

Using this evidence, Murray insinuates that eventually this would lead to a demand for larger ships. A typical trireme could not break through a barricade like the zuegma, so the Diodochioi created ships much larger and stronger which had the capability to do so. Classical Greek naval warfare was meant to defeat the opponent in a decisive battle at sea so that hoplites could land and the fleet could block supplies or assistance, they did not participate in the siege of the city. (Thucydides).

The Successor Kingdoms

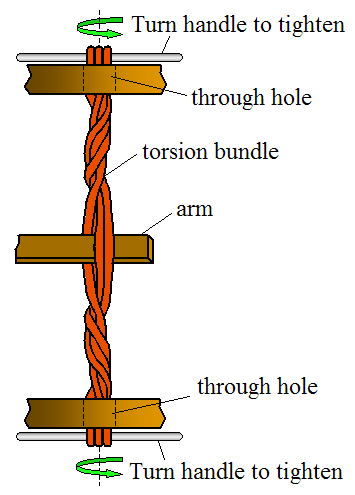

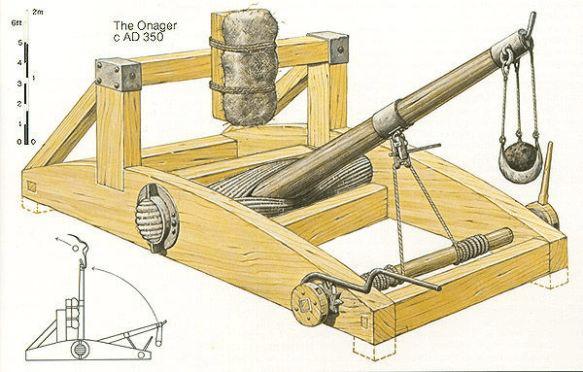

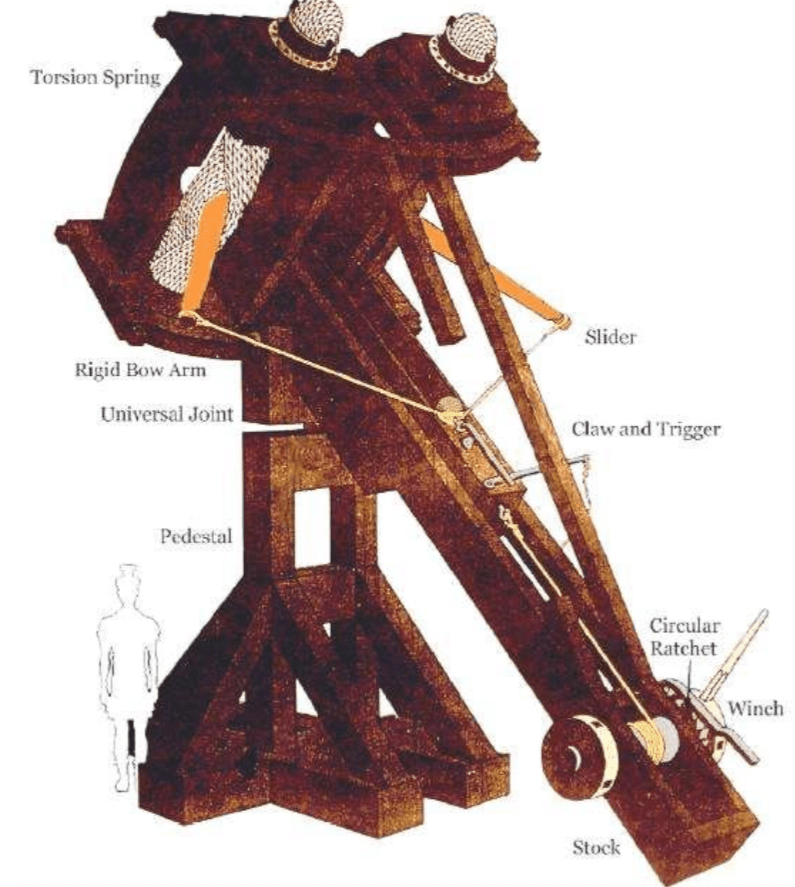

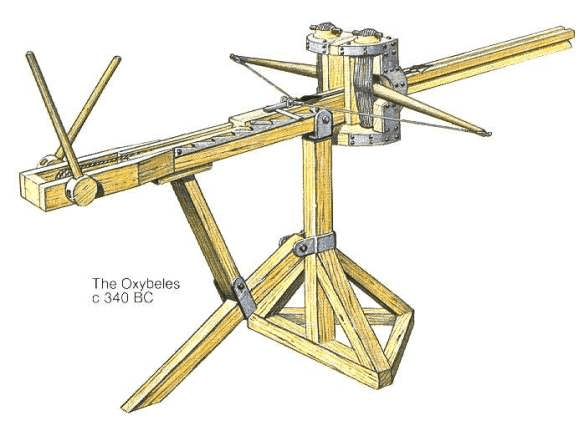

The nature of the Diodochioi’s holdings in their respective empires and spheres of influence transitioned their objectives, requiring the besiegement of coastal cities. This translated to the creation of vessels to complete these objectives. With the invention of torsion catapult technology, it became possible for navies to actively participate in sieges, shortening them significantly.

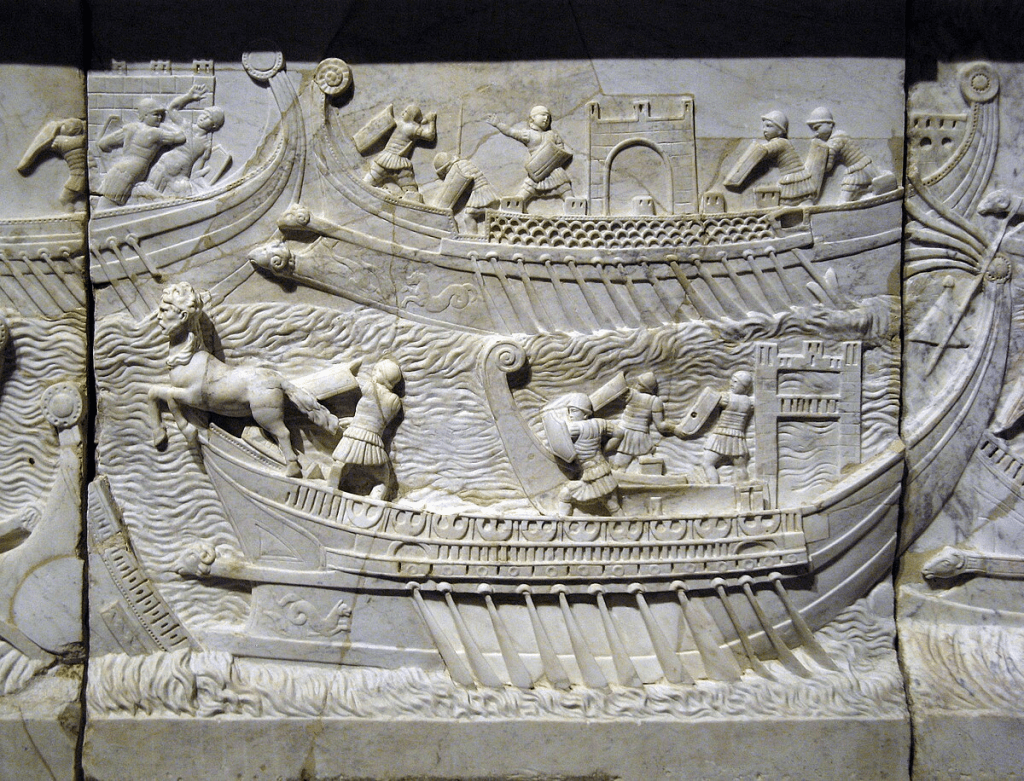

Subsequently, one of his main argument Murray mentions frequently are the introduction of new technologies, namely the bronze ram and the torsion catapult. These new ordinances created a demand for larger ships capable of utilizing this technology most effectively. In around 400 BC, the torsion catapult was introduced to the Hellenistic world during King Philip II’s campaigns by the Macedonian inventor, Diades of Pella; consequently, this piece of technology would change warfare and sieges by land and by sea forever. Philip II blundered by underutilizing his navy during his failed siege of Byzantion, Alexander the Great would learn from his father’s mistake. Equipping siege equipment to warships was revolutionary, and demonstrated during Alexander’s Siege of Tyre. Between the years 339 and 334 the Macedonian engineers, including Diades, refined their designs to fit on warships. At Tyre, “threes” and “fours” were lashed together to create platforms for catapults, ladders, assault towers, soldiers and rams which Alexander used effectively to defend his causeway and attack the city. Once his navy had been “transformed”, Alexander and his men took Tyre in a matter of months, this proved to the world the unprecedented capabilities a powerful and dynamic navy provides. Alexander the Great is naturally the character that all of his successors wish to emulate; therefore, this proven strategy spurred an arms-race between the Diodochi for the years to come.

Changes in Tactics

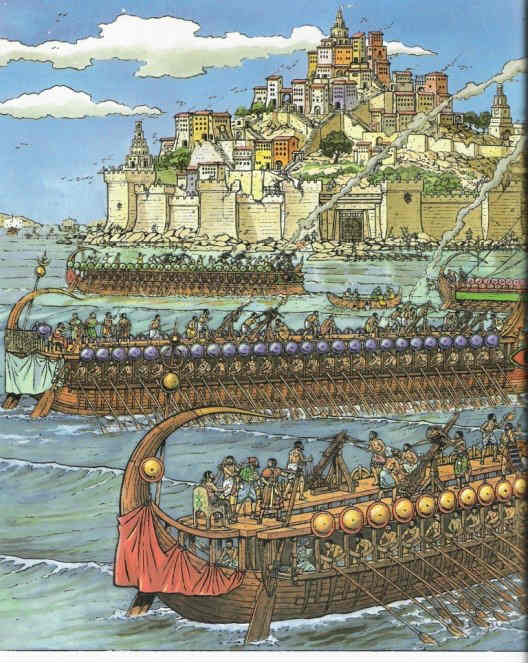

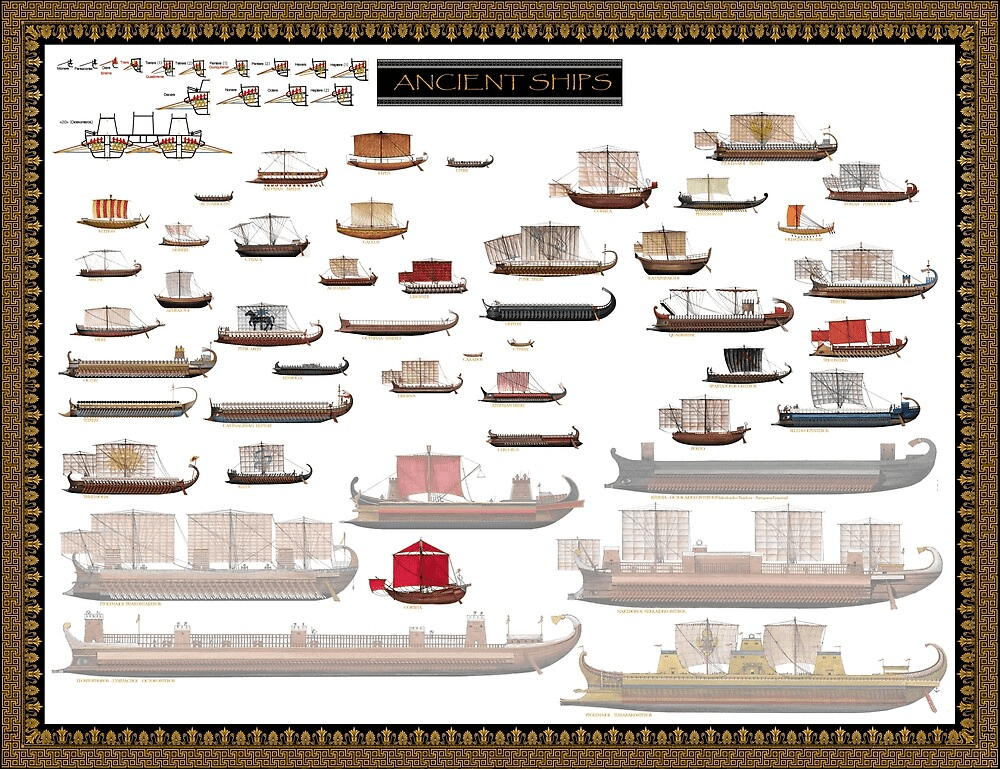

A great relic discovered was off of the coast of Israel in 1991 known as the Athlit Ram, which provided historians and archaeologists insight to a newly mass produced weapon utilized in Hellenistic naval warfare, the bronze ram. According to Thucydides, in the Classical era frontal ramming was not common due to timber rams and prows posing a risk of splintering or critical damage. Usually when a trireme pointed itself at its opponent it was a defensive position, since prow to prow rams commonly resulted in the sinking of both ships. With the vast resources the Successor Kingdoms drew from their treasuries, they were able to mass-produce a casted bronze that was ranked as “aircraft-quality” by modern experts. They used the “lost-wax technique” to cast these impressive rams to attach to their king’s naval vessels. Now that the prow was strengthened and the rams were more stable and devastating, this technology disrupted the status quo. A trireme versus a trireme in a prow-to-prow collision had equal chances of sinking, even a “four” (or quadrireme) to “three” collision proved risky. This is where we begin to see the introductions of larger class ships in the eastern Mediterranean. A larger ship, say a “five”, “six” or a “seven”, (or quinquereme, hexireme/sexareme, and septireme) equipped with bronze ram was able to ram smaller ships head-on in order to break their line.

Another advantage iterated in the book is that these larger ships had gunwales that surpassed the height of other ships, offering a strategic edge to the skirmishers on board.

“Often the weaker would kill the stronger due to their superior height, the stronger would be afflicted by the inferiority of their position and the unexpected nature of this type of fighting” (Diodorus).

Demetrius the Besiegers‘s battles against Ptolemy I near Cyprus demonstrated this advantage.

Entering the Era of Grandiose Polyremes

The sizes of these vessels were not only tactically significant, but the shock-factor they imposed was valuable in itself. Chapters five and six regarding the “Culmination of the Big Ship Phenomenon” depict warships as both used in conflicts, but also as a tool for foreign policy.

For example, Demetrius enjoyed much success in his campaign against Ptolemy I, he won decisive victories in significant battles. He and his father, Antigonos I Monophthalamus, were so elated with their success that after the Battle of Salamis they both proclaimed themselves kings. Demetrius did not only win territory or submission through pitched battle, his magnificent fleet of “threes” up to “sevens” and powerful siege equipment and artillery gained him the allegiance of many city-states in Cyprus, along the Cilician coastline as well as on the Ionian coast. This provides historical evidence that the magnificence of these ships and their size truly had a psychological effect on entire settlements, forcing them to yield without even fighting.

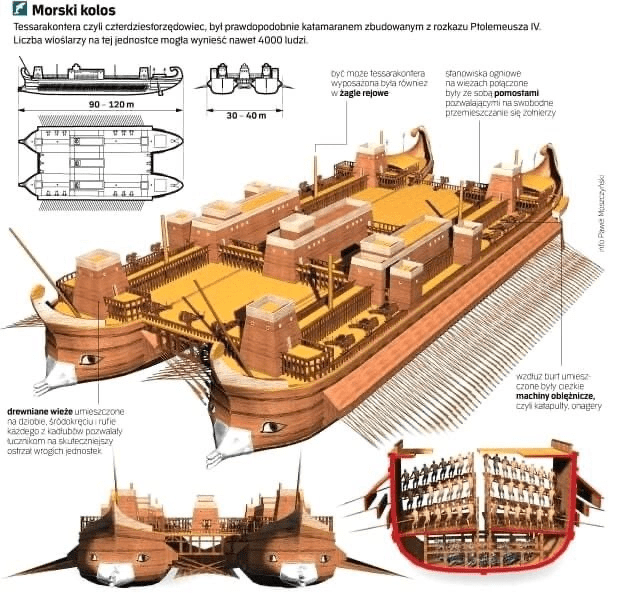

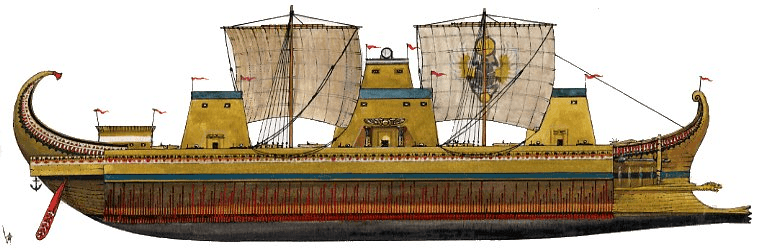

The Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt had the strongest big ship tradition. The fleet of Ptolemy II Philadelphius and Ptolemy IV Philopator were known to be vast and unique, with Ptolemy IV building a gargantuan tessarakonteres or “forty-rowed”, and Ptolemy II’s fleet consisting of 336 warships. In Plutarch’s, “Life of Demetrius” he described this massive ship and touched on its true purpose.

“Ptolemy Philopator built [a ship] of forty banks of oars, … she was manned by four hundred sailors, who did no rowing, and by four thousand rowers, and besides these she had room, on her gangways and decks, for nearly three thousand men-at‑arms. But this ship was merely for show; and since she differed little from a stationary edifice on land, being meant for exhibition and not for use, she was moved only with difficulty and danger.”

The Ptolemies used massive ships in their massive fleets as flagships only, to impress or frighten foreign powers. Murray compares this to the fleet of US aircraft carriers and stockpiling of nuclear weapons after World War II. While it is not entirely appropriate to compare two such unrelated eras of history; Murray’s point is clear, to create peace through superior firepower.

The End of an Era to Pragmatisism

According to Murray in chapter seven, “The End of the Big Ship Phenomenon”, as well as his analysis of primary sources from, the largest ship to be used in battle was likely an “eleven” or “twelve” in the early successors wars with Antigonos I in the eastern Mediterranean as well as the Battle of Chios during the Roman Republican period. Later in the Hellenistic period, when Rhodes, Pergamum and Rome became major players in the eastern Mediterranean, there were a succession of battles that saw polyremes defeated by smaller ships and “fives”. The battle of Chios, Battle of Corycus, Side and Myonnesus (all battles in the Syrian Wars) all were scenarios where smaller ships defeated larger ones. Finally, the true end of the era came at the Battle of Actium where Augustus and Agrippa defeated Marc Antony and Cleopatra with their Roman “fives”.

Synopsis and Analysis

The conclusions that Murray has come to are very convincing due to his use of equally convincing evidence and sound deduction. In lecture, I did not learn much about naval tactics or the variety of units and ships used in naval warfare, but I did learn much about the political landscape of the Hellenistic era and how the Diadochi interacted (usually violently) with one another.

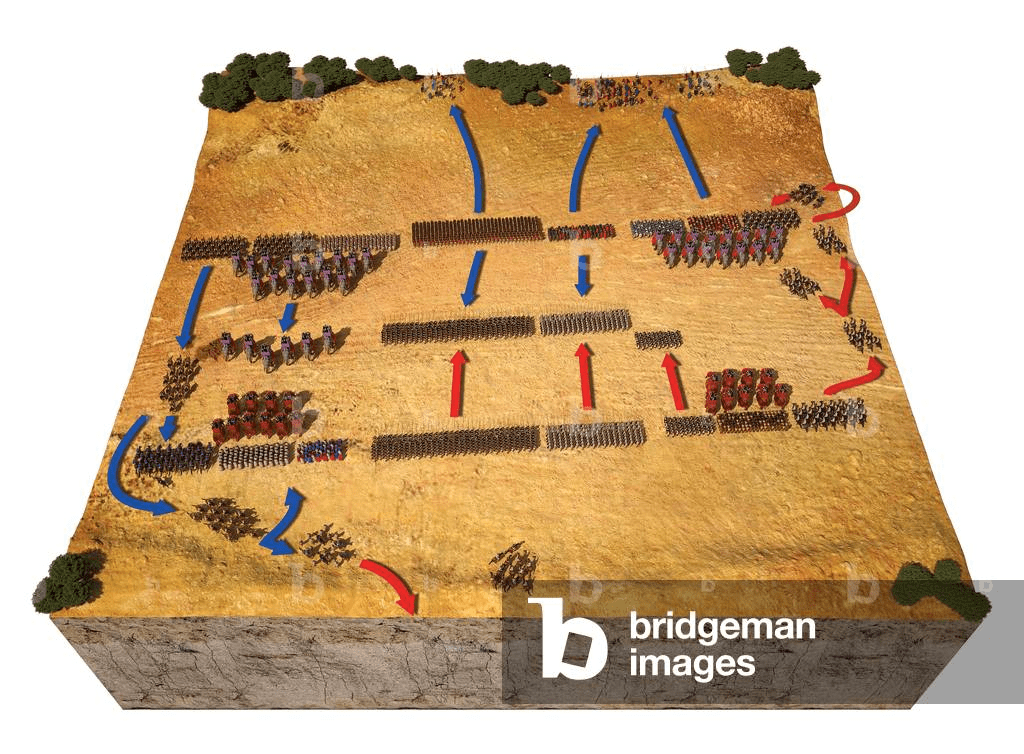

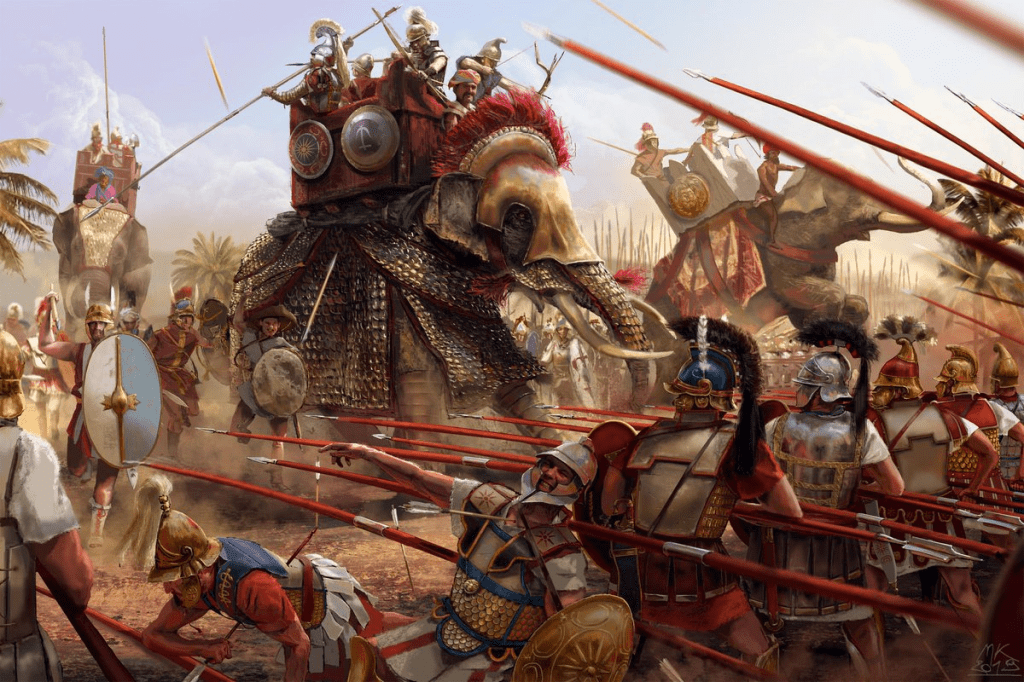

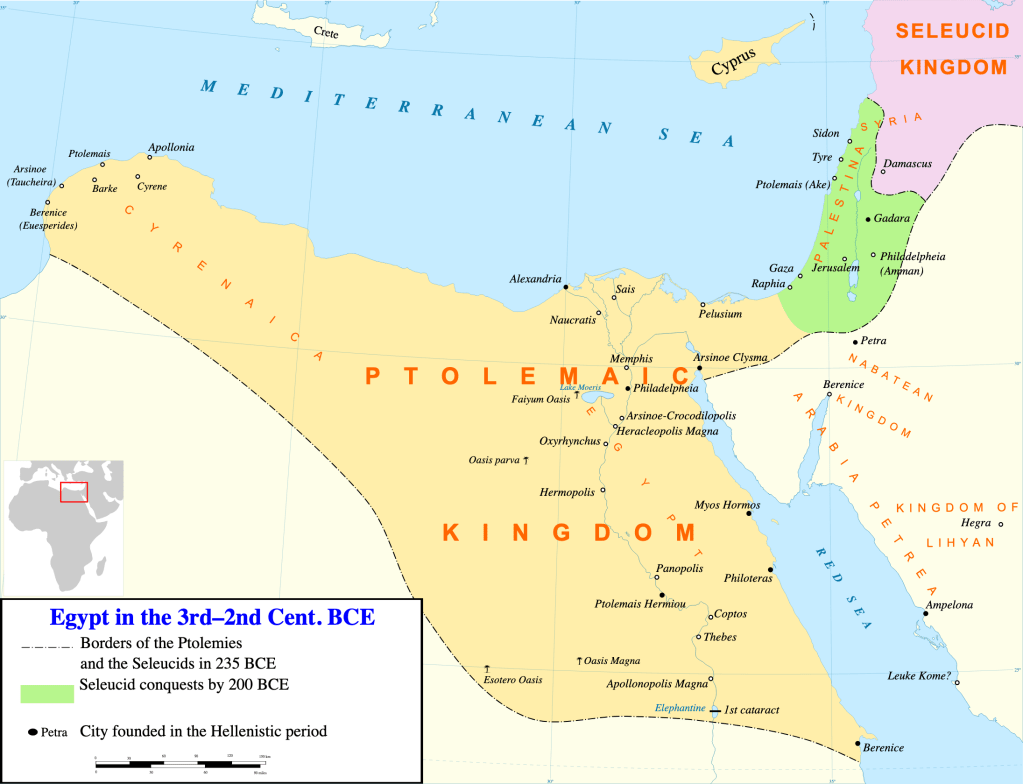

The section regarding the culmination of the big ship phenomenon was particularly interesting since it focused mainly on the Ptolemaic fleet. After the disintegration of the coalition of Diadochi upon the defeat of Antigonos I and Demetrius, the successors reverted to animosity among themselves. There are a couple factors which led to the significance of Ptolemaic naval culture. Firstly, The Seleucids and Ptolemies were particularly in conflict with one another throughout the Hellenistic period. Their animosity resulted in constant warfare with one another, exchanging territorial holdings back and forth for generations. Whenever a Ptolemaic king succeeded their father, the Seleucids would attack to test their mettle and capitalize on the power shifts. The most famous battles between the Seleucids and Ptolemaic Egyptians, such as Raphia (the largest battle of this period) and Gaza, culminated from the wars between Antiochus III The Great and Ptolemy IV.

Secondly; Alexander’s general, Ptolemy I had the advantage of establishing one of the first kingdoms for himself. Murray explains,

“Ptolemy established a secure kingdom for himself in Egypt, aided by he regions geographical isolation and extreme fertility. Of all the Diadochi, the first Ptolemy was least interested in territorial conquest, preferring to safeguard his kingdom by establishing a string of allied cities and garrisoned fortifications at strategic points around the shores of the eastern Mediterranean. Strategic points allowed him access to the raw materials needed to build and maintain a fleet, as they allowed him to safely block the ambitions of his rivals far from the borders of Egypt.” (Murray 191-193).

On page 192, Murray provides a map with Ptolemaic holdings in the early period. The map shows many dependencies from the Levant, the Cilician coast, Cyprus, the Ionian coast, and Thrace. Ptolemy II Philedelphius inherited his father’s strong navy, as he was crowned king the same year that Demetrius died. He continued to build upon it creating a naval tradition, with the tradition climaxing during the reign of Ptolemy IV Philapator.

Murray’s chapters on the end of the big ship phenomenon made a lot of sense as well. When the Diodochi and successors were fighting each other, bigger ships usually meant a better chance of winning. This was mainly due to the warfare Demetrius the Besieger presented, he used large ships to equip with artillery, missile units and siege equipment. These tactics were outlined in Philo the Byzantine’s tactical guide to naval warfare, one of the most valuable primary sources on Hellenistic strategy.

Regional Differences

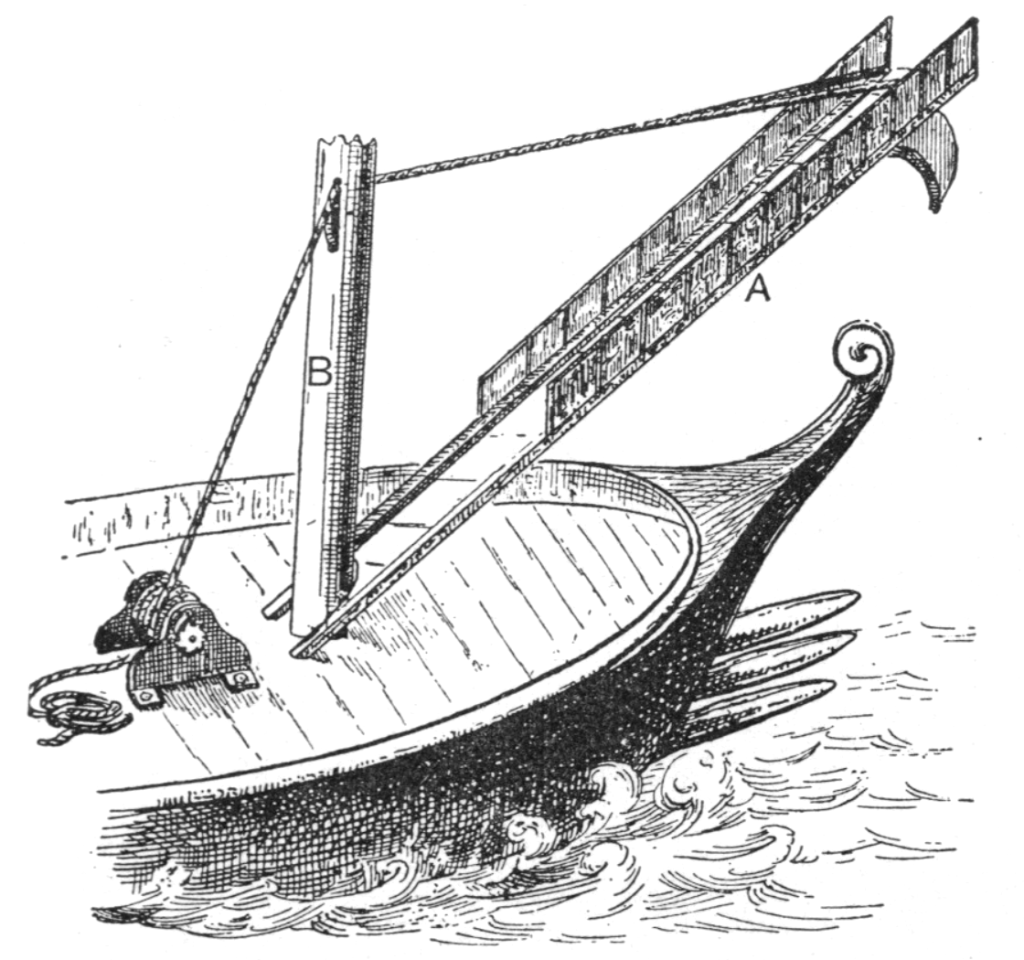

According to Murray, whereas the eastern Mediterranean experienced an arms race geared towards large polyremes with a focus on outfitting artillery and emphasis on ranged warfare, the western Mediterranean experienced a different developmental past. During the Hellenistic era in the west, Rome and Carthage were the principal regional powers who fought three wars for dominance. Murray describes the circumstances that led to Rome using smaller ships than eastern kingdoms. During the First Punic War, Rome needed to rely more on naval capabilities. A shipwrecked Carthaginian “five” provided blueprints that the Romans essentially copied for their own fleet. The Roman Senate commissioned the construction of over a hundred heavier “fives” (less maneuverable but more armored) along with a number of triremes to combat and defeat Carthage and expand into the eastern Mediterranean. Rome was not recognized as a power with impressive ships and sailors, but rather for the “valor” of their infantry (Murray 215-16, taken from Livy), so Rome developed the corvus, which was essentially a bridge on the ship with a metal hook to hold onto enemy ships for boarding. When Rome realized success in their boarding tactics, they perfected it and abandoned the corvus for grappling hooks. This was due to the increased risk of capsizing sine the corvus created a top heavy center of gravity.

Unlike the coastal siege capabilities of the successor state’s ships, the Roman ships were used to cut off supply lines and reinforcements to a siege by land. Therefore, a “power in numbers” strategy was used at sea, which nullified the need for gigantic polyremes. The battles of Corcyrus, Side, Myennesus and Actium all demonstrated larger ships being defeated by smaller ships and revised tactics.

Historiography

Sadly, many sources regarding the Hellenistic era have not survived into modernity leaving historians with nearly a century of history missing and up to speculation. However, Murray uses the works from primary sources provided by Livy, Diodorus, Plutarch, Philo the Byzantine and Thucydides. Murray also analyzed secondary sources provided by Lionel Casson and W.W. Tarn. Finally, he uses archaeological evidence based on the Athlit Ram, Augustus’ Victory Monument, relics at the site of the Battle of Actium as well as frescoes and art work to draw conclusions on the nature of naval warfare in this era.

The evidence Murray has used in his book are all relevant for his arguments, the primary sources are used frequently to prove his points and provide the reader with context regarding shifts in strategy over history. His secondary sources cited are meant to provide counter-arguments to Murray’s points, that he refutes using analysis of the primary sources. Lionel Casson is a more credible source to challenge than W. W. Tarn. Lionel Casson was a PH. D and a naval officer during World War II who completed his education at New York University as a classicist, where his area of expertise was naval warfare in antiquity. Sir W.W. Tarn was a Fellow of the British Academy who lived from 1869 to 1957. Many of his books and his arguments have been discredited by new discoveries or further analysis, he was also reputed for his intense biases of painting Alexander the Great as a “Scottish Gentleman”, in a way he viewed himself. His work has not all been discredited though, he has been given praise for writing histories on Greco-Bactria and Indo-Greeks, but these areas are far from the questions posed by Murray regarding Hellenistic navies.

Personal Criticisms and Praises

In order to provide better context for the reasons behind the massive naval arms race, due to his expertise, Murray could have provided some sources regarding the political animosity between the successors and deeper reasons for the wars they fought. I believe that this could have given the reader a better conception of the motivations behind spending massive amounts of resources on a navy, especially the massive flagships. In the anthology prepared by M.M. Austin, The Hellenistic World From Alexander to the Roman Conquest: A Selection of Ancient Sources that was used in lecture, there are many sources regarding the diplomacy, alliances and motives behind their actions and interactions.

On pages 92 through 98, Murray uses the sources written by Arrian and Diodorus that described the sieges of Miletus, Nicanor and Tyre by Alexander the Great. Murray allows the sources to speak for themselves, then he analyzes them to show how the battle tactics have changed from the era of Thucydides and that the Hellenistic era (starting with Alexander himself) has developed new tactics and technology to reach new objectives.

Also, Murray uses Philo the Byzantine’s book Mechanike Syntaxis, and its different sections regarding naval warfare and siege craft, expertly. Arguably this would be the best source to use as evidence regarding the proper strategies and tactics that were employed by Hellenistic naval commanders since this source is,

“systematic, scientific, and devoid of any political agendas” (Murray 192).

Murray used Philo’s recommendations to show that Hellenistic navies prioritized ranged warfare or ramming over boarding combat.

“The best deck fighters were skilled, practiced in fighting at sea and disciplined enough to rely on their ships ramming abilities and thus resist boarding the enemies.” (Murray 141).

Lionel Casson had a view of Hellenistic naval warfare as catapults firing at their opponent’s decks to clear marines, then to board, with victory being awarded to the fleet with the best marines. Murray uses Philo the Byzantine and historical accounts of battles to refute this.

Murray spends significant time citing and discussing the theories and work of Lionel Casson, who is rightly considered an expert on the subject. Murray specifically used arguments by Casson found in Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World and The Super-Galleys of the Hellenistic Age. Casson argues that marines decided the fate of battles, Murray argues against that sentiment. Lionel Casson says in Ships and Seamanship that,

“One feature above all others governs this stage of development: boarding now became an important naval tactic, and galleys more and more ceased to become man-propelled missiles to become carrying platforms for fighting men and a new naval weapon – catapults.” (Casson).

Although this is the most widely accepted reason behind the development of large polyremes, Murray disagrees with the consensus by citing sources from Philo the Byzantine and Livy, and figures regarding casualties of battles.

Admittedly, the Romans during the Punic Wars and Seleucid War undeniably preferred to grapple and board. I believe that this affected their cultural history making Roman authors biased towards the valor involved in boarding during naval battles. Also, the Romans were relatively late to come to the naval battlefield in the eastern Mediterranean compared to the successor kingdoms. However, figures provided by Arrian, Livy, Polybius and Diodorus about naval battles like Salamis, Chios, Actium, Myonessus and more provide a different narrative statistically. Many of these battles account for significant enemy casualties, but most of these battles record most of the casualties as victims of ramming, with Chios being a battle as high as 90% of casualties due to ramming (Murray 166). Also accounts of swamped or destroyed ships at Actium mentioned intense flaming missile fire and catapult stones. Most of the ships destroyed in Cleopatra’s and Antony’s fleet burned and were destroyed by missiles, this demonstrates further evidence that boarding did not take priority in many naval battles.

Earlier in the Hellenistic wars between the Diocochi naval battles were characterized by ramming and missile fire. For example, in the battles between Demetrius and Ptolemy ships as large as “sixes” were utilized to frontally ram Ptolemy’s ships on his right wing. Also, these large ships could have been used to smash through lines of smaller ships, sheer off oars, and use their height advantage to throw missiles down on the ships adjacent to them, as described by Diodorus. Finally, Philo the Byzantine advises not to engage in boarding unless absolutely necessary. The most valuable sailors according to Philo are ones who are willing to take on more of a defensive posture to fight off boarding attempts and “resist the urge to board”, while their ship can reposition itself to ram. Superior oarsmen and missile superiority paired with disciplined defenders take the day in Philo’s opinion as well as in historical instances of battles.

I find both arguments persuasive, but based on the evidence presented by Murray, it seems that the Romans were the ones who relied most on boarding, yet that was not demonstrated at Actium.

Overall the book, The Age of Titans: Rise and Fall of the Great Hellenistic Navies by William H. Murray, was intensely informative. The use of different types of sources give the reader a comprehensive glimpse of how historians write books like these. The archeological evidence complimented or rebuked written sources, different modern historians and their respective analyses, and the authors attempt to use all of these to create their own synopses remains fascinating. Murray writes his book well by connecting his evidence directly with chronology and analysis. I would recommend it to anyone with an interest in the navies of antiquity. Regarding weaknesses, Murray tells the reader much of Demetrius’s, Roman and Ptolemaic naval culture but does not touch on the other Hellenistic reasons for building these ships other than to keep up with their opponents.

Leave a comment